For jazz pianist and composer Kenny Werner, music’s ability to lift people out of even the most crushing of circumstances is not at all an abstract concept.

On October 2, 2006, Werner and his wife Lorraine received the call all parents dread: their 16-year-old daughter Katheryn had lost control of her car and did not survive the rolling crash.

Months of numbing grief went by. At first, even at a Puerto Rican getaway gifted by a kind friend the couple found they could barely get out of bed. Then, Werner told Jazz Times, they tentatively turned to their longtime Siddha Yoga chanting and meditation practice.

“That’s when it began to elevate my consciousness,” he said. “In the middle of this pain, there would be these odd moments of inspiration. Seeing the whole thing in a different way. And in one of those moments, I wrote the poem ‘No Beginning, No End.’ And that’s when it all unfolded for me.”

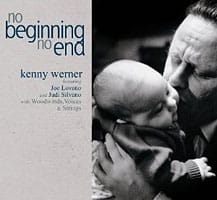

What unfolded were the compositions—bigger, more emotionally complex than his jazz writing, scored for small orchestra and voice—that would form the body of Werner’s 2010 album, No Beginning, No End. The title piece, he says in an interview for an as-yet-unfinished film about birthing the record called Uncovered Heart, “That’s all real life. It’s about transition from life to death and death to life in different planes of existence.”

What unfolded were the compositions—bigger, more emotionally complex than his jazz writing, scored for small orchestra and voice—that would form the body of Werner’s 2010 album, No Beginning, No End. The title piece, he says in an interview for an as-yet-unfinished film about birthing the record called Uncovered Heart, “That’s all real life. It’s about transition from life to death and death to life in different planes of existence.”

Elsewhere in the clip, Werner describes two other pieces on the album, Visitation and Cry Out, with unvarnished honesty:

“[They’re] two sides of how a human can perceive death. One is the sort of transcendental side, understanding it’s a journey, understanding that the journey continues, understanding that the connection between souls continues. And the other is as a reasonably, typically unenlightened human, which I am very much of the time, and that’s anguish.”

When No Beginning, No End was released, John Kelman at All About Jazz, echoing many other critics at the time, said, “Few albums have ever so clearly demonstrated the healing power of music,” calling it “a rare masterpiece.”

Werner says he has always felt tuned in to the spiritual side of music, and that relationship to the mystical nature of sound continues to evolve. Last May he performed a duet called Engaging Compassion: A Musical Meditation with vibraphonist Dick Sisto, a longtime Tibetan Buddhist practitioner, to open a talk on the same subject by the Dalai Lama. He has also contributed to an album of music to enhance Siddha Yoga meditation, and has gained global renown for his book and attendant workshops entitled, Effortless Mastery: Liberating the Master Musician Within.

Triple Grammy-winning bassist Esperanza Spalding will share the stage with the Kenny Werner Quartet for the Concert to Feed the Hungry, with all proceeds supporting Buddhist Global Relief’s worldwide projects to eliminate hunger and its causes.

For further exploration about Kenny Werner, visit his website, and check out this interview with the Redwood Jazz Alliance in which he tells how hearing Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way was his gateway to the deeper currents of sound, and his riff on why accomplished jazz masters like Herbie Hancock still seek Buddhism and other spiritual paths.