Songs of Kabir

By Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

New York Review Books Classics, 2011; 144 pp., $14 (paper)

If you’re a fan of Hafiz or Rumi (said to be America’s favorite poet), you’ll love the fifteenth-century Indian poet Kabir, for he is wilder, sweeter, more radical, and more hopelessly love-intoxicated, if you can imagine that. My favorite quote in literature belongs to him—I laugh when I hear that the fish in the water is thirsty—in which he smiles at everyone searching for enlightenment while living immersed in the absolute. Kabir brims with such wise, witty reflections.

Those who already know Kabir will meet a leaner, more postmodern poet in the new Songs of Kabir, translated by the Indian poet Krishna Arvind Mehrotra. Those who grew up with Robert Bly’s The Kabir Book of the 1970s, which made Kabir famous in the West, may even wonder if they are reading the same poet. But like the myriad forms of the Divine in the Indian pantheon of gods and goddesses, Mehrotra’s translation assures us that Kabir’s legacy will always be unpredictable, ever-branching, and thrilling to watch unfold.

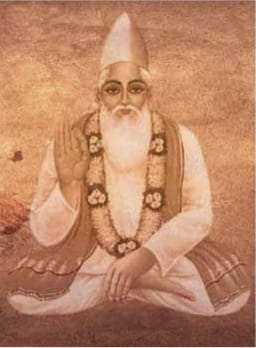

Kabir sought (and many would say found) enlightenment through bhakti yoga, a path characterized by ecstatic love. Bhakti is a branch of the overarching umbrella of spiritual systems known as Hinduism (actual name sanatana dharma, the “Eternal Truth”; Western invaders coined the term “Hindu” after crossing the Indus River). The goal of bhakti is surrender of the self and annihilation of the ego on the altar of love. A bhakta, one who has fallen in love with the Divine, sings songs, writes poems, plays music, and dances for the Beloved. One might sing to Krishna, Shiva, Kali, or Sarasvati—or Jesus, the Buddha, or your guru—or a mountain, as Ramana Maharshi did for Arunachala. Hindu cosmology features countless gods and goddesses, all of which are simply images for the one infinite consciousness pervading the universe—the unconditioned absolute reality called Brahman, or the (Universal) Self. The many images provide the means of approaching the unapproachable, conceiving the inconceivable, adoring the transcendental. Ultimately, all names and forms fall away in the final vision of enlightenment.

The term bhakti first appeared in scripture in The Bhagavad Gita. There, Krishna, avatar and divine incarnation, counsels the warrior Arjuna before a battle, and, in the course of explaining the meaning of life and death, describes different paths of yoga. While all lead to enlightenment, Krishna says bhakti is the sweetest and easiest—easy, as long as you’re ready to surrender all attachments and the self itself. The nineteenth-century bhakti guru Ramakrishna emphasized that your love must have the intensity of a drowning person gasping for air. The bhakti path emphasizes personal devotion, spontaneous expression, and sometimes unorthodox practices. It is often critical of rigid dogmas, sectarianism, and empty rituals.

In the sixth century, a bhakti movement arose in southern India and spread throughout the subcontinent, flourishing in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries in the northern India of Kabir. We know relatively little about the person Kabir. Tradition has it he was born in the holy city of Varanasi into a Muslim family of weavers, and after his death he was claimed by both Muslims and Hindus. While he called his God “Ram” rather than “Allah” and may have followed a Hindu gurureformer named Ramananda, he freely castigates Hindu pieties, rituals, and the whole caste system.

Among the thousands of poems attributed to Kabir, not one can absolutely be identified as his. No original manuscripts exist, as his poems were transmitted orally. And to complicate matters further, singers in this improvisatory tradition, like jazz musicians, would riff on his lines, altering or expanding them. As Arvind Krishna Mehrotra says in his introduction, Kabir’s “is a collective voice that is so individual that it cannot be mistaken for anyone else’s.”

I was introduced to Kabir in college in the late 1970s, when I was beginning my own journey on the bhakti path. A professor gave me a copy of Robert Bly’s The Kabir Book. Bly called his renderings “versions,” because rather than translating from the Hindi, he took the earlier translations of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore and rendered them into contemporary American English.

I was spellbound. Kabir instantly became and has remained my favorite poet.

His lines stirred my heart and often broke it: “Kabir says: Listen, my friend, / there is one thing in the world that satisfies, / and that is a meeting with the Guest.” “The Guest who makes my eyes so bright / has made love to me.” “Student, tell me, what is God? / He is the breath inside the breath.”

But Kabir is not only a devotional poet, the aspect captured so surely by Bly. He is also a reformer and critic, and in Mehrotra’s new translations, it is the rebel who steps forward. Perhaps like Homer and Dante, Kabir must be remade for each age, and so he speaks in Mehrotra’s translations with a new and markedly postmodern voice. The preface by Wendy Donager sees Kabir as a kind of deconstructionist, toppling hierarchies of religion, caste, gender, and ultimately the idea of a God with form. She emphasizes what is called Kabir’s “upside-down imagery,” as in, “A mother delivered / after her son was,” and notes that Mehrotra’s “slang, neologisms, and anachronisms … are a brilliant means of conveying much of the shock effect that upside-down language would have had upon Kabir’s fifteenth- century audiences.”

Student, tell me, what is God?

He is the breath inside the breath.

— Kabir

Mehrotra’s Kabir certainly shocks. He lectures, warns, and chastises: “My home, says Kabir, / Is where there’s no day, no night, / And no holy book in sight / To squat on our lives.” Reading these “disruptive, oppositional” poems, says Mehrotra, is like receiving a “well-directed blow to the head.” Many feature violent, if humorous, imagery, which may be Kabir’s or may be Mehrotra’s, given the improvisatory tradition. “Even death’s bludgeon / About to crush your head / won’t wake you up.” Poems warn of the approach of death and the vanity of human desires. “Bedridden with a stroke, / You make a rattling sound / And wish to make amends. / You’ll leave this world, says Kabir, / Picked clean.” And like singers through the centuries, Mehrotra wittily improvises and modernizes the language: “’Me shogun.’ / ‘Me bigwig.’ / ‘Me the chief’s son. / I make the rules here.’ / It’s a load of crap. / Laughing, skipping, / Tumbling, they’re all / Headed for Deathville.”

Happily, within this volley of shocks, we find some beautiful images: “Put the bit in its mouth, / The saddle on its back, / Your foot in the stirrup / And ride your wild runaway mind / All the way to heaven.”

Yet, with all the flair and energy of this new collection, I feel something is missing. We are warned of the dangers of walking the wrong path but less strongly feel the joy of the right one. Yes, Kabir sought to shake us out of complacency and dogmatism. Yes, he satirized notions of caste, gender, and sect. But how many times need we be reminded of the noose of death hanging over us? I read and wonder, where is Kabir, the lover? Perhaps the voice of selfless love and devotion feels out of place in a postmodern sensibility.

Robert Bly’s Kabir too is radical, funny, and iconoclastic, and this side of him provides much of the delight. But he’s not only an iconoclast. The greater part of him is a lover and a friend. Love is everywhere on his lips. He pines, dreams, cries out for love, thrills, leaps at the Beloved’s touch. “The Guest, who makes my eyes so bright / has made love to me!” “Kabir saw that for fifteen seconds, and it made him a servant for life.”

Mehrotra explains that he is working from a different Kabir manuscript than the one Tagore used for the translations Bly relied upon, and that this accounts for much of the difference. John Stratton Hawley, in an afterword to the most recent reissue of Bly’s Kabir: Ecstatic Poems (2004), explains how the Kabir legacy branched into two different traditions in eastern and western India: “The western Kabir is far more intimately, devotionally (bhakti) oriented than its eastern counterpart…” In the eastern we find “the salty, confrontational Kabir…. He goads, he berates, he challenges.” Perhaps, then, Bly’s Kabir is simply more western, and Mehrotra’s more eastern.

As traditions within Indian spirituality allow us to choose an image of the Divine that most appeals to us, so it seems we get to choose the Kabir we like best, too. For more than thirty years I have returned again and again to Robert Bly’s Kabir, for he is wildly, hopelessly, ecstatically in love. He topples icons, but that’s mostly because of the dancing. And perhaps Kabir, the enemy of dogmas and certainties, would enjoy nothing better than to see our trouble in pinning him down and figuring him out.

How to choose? Read both versions and see which gives you wings. Then ride that one all the way to heaven.