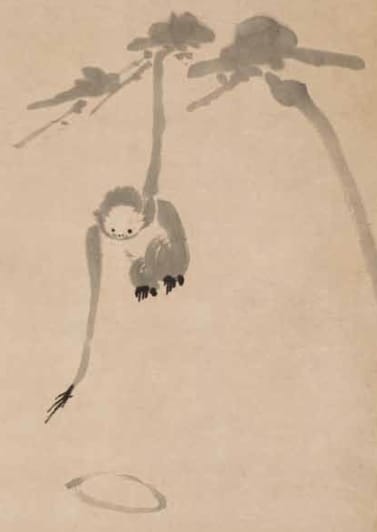

Hakuin Ekaku: Monkey Catching the Moon, Ink on Paper. From the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria collection.

Hakuin Ekaku: Monkey Catching the Moon, Ink on Paper. From the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria collection.Can animals meditation? Steve Silberman discusses the possibility, using sutra and science alike.

Images of animals gathering to listen to the Buddha’s sermons are traditional in Southeast Asia, where a body of folklore called the Jataka Tales recounts Shakyamuni Buddha’s pre-human incarnations. But do animals actually meditate? Many cat-owners – seeing their beloved felines at rest in a shaft of sunlight, with paws in full lotus and eyes half-lidded – would say yes. Yesterday on National Public Radio, Robert Krulwich of the supremely lively science show Radiolab interviewed a biologist who may have witnessed something like collective baboon samadhi.

Primatologist Barbara Smuts has spent 25 years in the jungles of Kenya and Tanzania, observing baboon behavior. She has watched the animals fight, hunt, flirt, and mate, and gradually, they have come to accept her as one of their own. One day several years ago, however, Smuts saw a kind of behavior she’d never seen before. A troop of Gombe baboons were en route to the trees where they sleep when they passed a small stream. In a paper for the Journal of Consciousness Studies, Smuts described what happened next:

“Without any signal perceptible to me, each baboon sat at the edge of a pool on one of the many smooth rocks that lined the edges of the stream. They sat alone or in small clusters, completely quiet, gazing at the water. Even the perpetually noisy juveniles fell into silent contemplation. I joined them. Half an hour later, again with no perceptible signal, they resumed their journey in what felt like an almost sacramental procession. I was stunned by this mysterious expression of what I have come to think of as baboon sangha.”

While no one knows what was really going on in the monkey-minds of the baboons that day (Krulwich’s cohost Jad Abumrad sounds skeptical that anything special was happening at all), the experience left Smuts profoundly moved, convinced that observant humans can attain a shared state of understanding with animals that she calls “intersubjectivity.” “I felt as if I got a glimpse into a part of baboon life that humans just don’t get to see,” Smuts tells Radiolab.

In Praise of Ch’an Master Wang

You who Cares for the Bonnet Monkeys around his Mountain StudioFrom

Tree after tree

In the undisturbed courtyard

The fruit’s dropped

On the frost.

They even love

Entering the thatched hall

To listen to Dharma. How is it

Other species know courtesy

And limits?

Coming in each time,

They sit opposite one another

On the meditation benches.–Chi Yuan (late 10th century)

I suspect that many folks who have chosen to live their lives in 24/7 reciprocal relationships with non-human social mammals have noted these rare – but not unknown – times when our sentient peers will enter into that introspective, quiet, meditative state. With foundational authorities such as Dr. Damasio explicitly recognizing that self-awareness is far from unique to hairless bipeds – finally – we really cannot be surprised that other self-aware critters will seek those quiet spaces between the past and the future, from which to seek integration with the external world.

A Rottweiler partner of mine, Fritzy (originally rescued from a nasty situation at 12 months old), developed the habit and took these quiet periods with more regularity than any of my other canine associates thus far. Generally in the evening, he'd seek an out-of-the-way location with a good view of the back of our farm. Once there ,he'd sit squarely and resolutely, staring out to the horizon: no movement, no slouching, no inattention. These "Fritzy moments" were on average 20-25 minutes long.

Interestingly enough, the rest of our canine family was always careful not to disturb Fritzy when he chose these quiet times to think – I never had to ask them to give him that space, they all simply respected the work Fritzy was doing. Sometimes, if things were quiet, I'd walk out and sit down next to him – he'd glance at me, a look that said "I don't really want to talk right now, but you're welcome to stay if you can keep quiet." I accepted those conditions; Fritzy and I would then share a few tens of minutes of quiet contemplation together. Only the most pressing of demands could interrupt us; otherwise, we stayed until Fritzy said he was done.

He'd get up, look around as if from a trance, shake himself, say "hello" to me quickly before heading back to the barn and the rest of our social world. Afterwards, he had a certain spring to his step – one could not but feel that those meditative breaks helped him bring a peace to his internal environment which was sometimes lacking, otherwise. Fritzy was a complex dog, all his life – it was only in his older years, after he turned 8, that he developed his meditative practice. It really did seem to be healthy for him; without it, he could become somewhat brittle and antisocial with the rest of us.

Was this "really" meditative work he had taught himself to do? What was he "really" thinking and feeling in those self-chosen, quiet periods? I can offer no more authoritative an answer to those questions than can any one being claim such about another being – of whatever species. However, after a decade of deep partnership and mutually reciprocal empathy between the two of us, my ability to "see through his eyes" was certainly not an illusion. Perfect? No – but is any of us possessed of perfect understanding even of our *own* mental states? No.

Over time, a few of our other canine family members seemed to take interest in Fritzy's work – our older, rescued Great Dane stud dog, in particular, eventually came to sit alongside Fritzy and partake of his own meditative experiences (never closer than about 15 feet apart). Lazarus, so named because he died while his mother was whelping him and was brought back to life only via CPR, is as complex and occasionally troubled as Fritzy though of course in his own unique ways. Perhaps it's the experienced the "rescue dogs" have in seeing the horrors of human evil firsthand; our non-rescues who have lived lives always filled with love and caring seem far less interested in self-guided meditative work. For whatever reason, Laz now has his own practice – not as consistent as Fritzy's became, but every few months I'll see him off on a nearby hillside, staring at the horizon from a perfect, composed, proud "sit."

Fritzy died, an old and happy and deeply loved member of our family. From his painful early life through his central role in our family – and a decade of deeply intimate emotional and physical relations with me – he traveled a long and complex canine life path. He taught all of us who shared that path with him so much; his meditative breaks taught me more about genuinely healthy "quiet work" than any book or article I've ever read. Years after losing him to death, I recall his presence and courageous grace each and every time I compose myself for a meditative experience. He's gone, but not really gone for me – though I still miss him and the love we shared, every day of my life.

Nobody who knows horses deeply will be lacking stories of their approaches to meditative peace; it seems far more common in the species than in the carnivorous canines (& humans).

Regards,

Fausty | http://www.zetawisdom.net