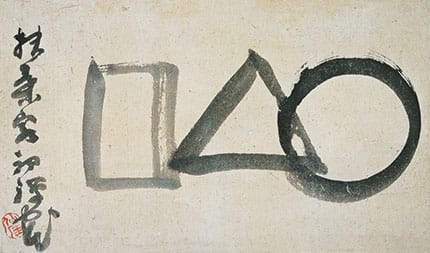

Zen Master Sengai (Scheidegger & Spiess 2014) showcases the paintings of Sengai Gibon (1750–1837), the famous abbot of Shofukuji, Japan’s first Zen temple. A man of many talents, Sengai became especially well known for his ink paintings. But as contributor Hirokazu Yatsunami tells us, at age eighty Sengai decided to give up painting altogether, saying he was deeply ashamed of his works and believed it would be better if they were swallowed by the sea. The hiatus didn’t last and he soon revisited his talent, continuing to paint until his death. Sengai’s pieces are often described as didactic, and they include inscriptions that mix play and insight. Yet as Michel Mohr explains in his contribution to the volume, past audiences have read these inscriptions in radically different ways. D. T. Suzuki’s English translations illustrate this point well: Sengai’s famous painting of three geometric figures—a square, a triangle, and a circle—includes an inscription that reads “Japan’s first Zen monastery,” followed by a signature. Suzuki renders this “the Universe,” a far cry from the literal meaning and indicative of the vast range of reactions Sengai’s art has inspired.

Ian Harris’s Buddhism in a Dark Age: Cambodian Monks Under Pol Pot (Hawaii 2013) investigates the fate of Cambodian Buddhism under the brutal Khmer Rouge regime. During its reign from April 1975 to January 1979, the Khmer Rouge devastated Cambodia’s monastic communities, dismantling its Buddhist institutions and carrying out the defrocking and murder of vast numbers of monks. Despite the Khmer Rouge’s persecution of Buddhists, Harris shows how, paradoxically, certain dimensions of their regime took after Buddhist tradition: leader Pol Pot (who claimed to have spent six years in a Buddhist monastery) consistently extolled familiar Buddhist ideals such as discipline and self-transformation; he commanded his information minister to ensure that radio announcers delivered propaganda as though chanting “like monks who lead the prayers at a wat”; and he used the Khmer term for dependent origination to translate Marx’s dialectical materialism. Such tactics, Harris reasons, were intended to make the messages of the Khmer Rouge more comprehensible to a traditionally Buddhist population. In addition to discussing the period in which the Khmer Rouge were in power, Harris also describes the events that led up to their ascendancy and Cambodian efforts to rebuild Buddhism in the years that followed.

Peter Jaeger’s John Cage and Buddhist Ecopoetics (Bloomsbury 2013) explores the ecological and Eastern dimensions of the work of the late American composer, writer, and artist John Cage (1912–1992). Cage famously took cues from his readings in Zen Buddhism and attempted to remove his intentions from his compositions by relying on the chance operations of the I Ching. Using similar techniques to determine the layout of his book (which features multiline gaps within sentences that were generated by an I Ching-inspired online random-integer generator), Jaeger collapses distinctions between his analysis and its subject matter. The result is a surprisingly liberating reading experience that mixes talk with silence, reminding us of the Zen teachings that inspired Cage’s creations.

Himalayan Passages (Wisdom 2014), edited by Benjamin Bogin and Andrew Quintman, presents papers written in honor of Hubert Decleer, who occupies a special place in the hearts of many Tibetan and Newar studies scholars. For a quarter century he has directed and advised the School for International Training’s Tibetan studies program in Kathmandu, welcoming nearly a thousand students to Nepal and inspiring many to take up the study of Tibetan and South Asian literature. Jacob Dalton, a former student of Decleer and now a professor of Tibetan studies at UC Berkeley, has remarked on Decleer’s talent for turning seemingly dry historical investigation into “a case worthy of Sherlock Holmes.” Decleer’s avid curiosity was what brought him to Asia in the first place: after hitchhiking from Europe to South Asia in 1963, he led luxury overland tours along the same route before finally settling in Kathmandu, where he has spent his days writing and teaching.

Centuries ago in Japan’s Hirama province, a rice farmer lost his wife, and with his grief came worry about where she had gone in the afterlife. He gave up his rice paddies, took ordination as a Buddhist monk, and lived in a shabby hut facing the sea, where he constantly prayed for her, relying on sympathetic villagers to bring him food. One day he announced that he was about to die, but no one believed him. As the story goes, he died as he predicted and was found in his hut with his hands folded, facing west, and a strange cloud floating above him—all signs of his enlightenment. The medieval Japanese compiler of this story reflects: “It was extraordinary that this monk devoted his life to praying for his wife. It is most wonderful that the monk attained enlightenment. How could his wife fail to be delivered when he, who had prayed for her, successfully attained enlightenment himself?” This and other moving stories make up The Senjusho (Kanji Press 2014), introduced and translated by Yoshiko Dykstra.

“Don’t say that a stomach cramp is less than pleasant. Say that it hurts.” This is how Ben Howard, emeritus professor of English at Alfred University and longtime Zen practitioner, explains Ernest Hemingway’s fourth rule for writing (“Be positive, not negative”). Rather than urging us to smile and be happy, Howard says that Hemingway was “telling us to render the present reality in the most direct way.” In The Backward Step (Whitlock 2014), Howard incorporates fiction, poetry, social media, snow shoveling, and U.S. politics into his reflections on Zen practice, offering short and perceptive essays that are a pleasure to read.

Intellectual Dharma does not see what transcends intellect.

Fabricated Dharma does not realize what “nonactivity” means.

If you wish to attain “transcendence of intellect” and “nonactivity”

Cut the root of your mind and leave awareness naked.

For commentary on these and other verses from the Indian adept Tilopa (988–1069), check out Sangyes Nyenpa’s Tilopa’s Mahamudra Upadesha (Snow Lion 2014), translated and introduced by David Molk.

[…] Book Briefs […]