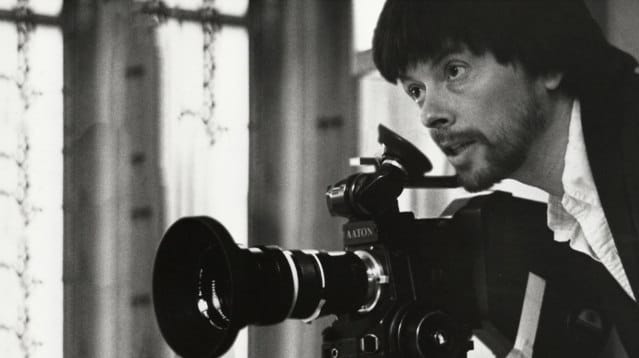

Photo via Craig Duffy.

Photo via Craig Duffy.Filmmaker Ken Burns — certainly one of the most influential American historians of our day — has become outspoken about current events as they relate to the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump: in his commencement address at Stanford yesterday, Burns called Trump “glaringly not qualified” and said that “As a student of history, I recognize this type. […] Edward R. Murrow would have exposed this naked emperor months ago. He is an insult to our history.”

In this throwback from our archives, we find Burns in a 1997 conversation with Mark Gerzon, author of A House Divided and co-founder of The Common Enterprise, and Molly De Shong, former managing editor of Lion’s Roar. In it, we get a glimpse of Burns’s artistic and intellectual priorities and processes which, as a “student of history” have always been geared to answerting a key question about America: Who are we?

Mark Gerzon: What do you think it is about your work that allows it to transcend partisanship and parochialism?

Ken Burns: Well, let’s acknowledge that in the United States what we call partisanship constitutes a pretty narrow band. I mean, in a place like Italy you find people who are close to the Red Brigades on one end and to Mussolini on the other. That’s a span which would take a great deal of bridging, and I don’t think we feel that kind of difference here between even the most rabid members of each party.

Having said that, what my work is about is that we have an opportunity to observe the workings of the universe on the principles of yes and no, and that growth, realization, even truth, occurs when something is seen beyond that mechanism. Even those who engage in day-to-day partisanship must suspect that there is a larger engine for which they are merely the fuel.

It is not so much a question of choosing between Democrat or Republican, or yes or no, or black or white, that actually matters, but that anyone who might, through stumbling into it, perceive the dynamic can attract an audience without being accused of being mushy or in the middle, which is certainly not my place.

Mark Gerzon: I was working on a book about contemporary America, and quoted Lincoln about “a house divided.” The Civil War became a metaphor for me about what was going on today, and then suddenly, there was your series.

Ken Burns: What is interesting is how foolish it would be to think that we’re actually dealing with the past. We are not. These are not séances; these are not regressions that we are doing. In fact, the past is gone; there’s nothing in our study of Lincoln that will affect the past. So history is not about the past, but about the present. Faulkner understood this; he said that history is not “was” but “is.”

It seems to me that since we do not affect the past, the only cause for investigating history is that somehow in our investigation we might create a great mirror in which we can see ourselves reflected. History is each generation’s attempt to rediscover that part of the past which gives this present new meaning and new possibilities.

So if one is searching for the soul of America—and I’m doing it and you’re doing it in various ways—we’re going to be led inevitably to a moment in the past which we decide was the defining moment for the country. The Civil War is the traumatic event in the childhood of the nation: distort as we might, disguise it as we so often do and ignore it, nevertheless it has powerful consequences for the present, not dissimilar from the death of my mother when I was young.

Mark Gerzon: Then is it possible to make a film about the future, or is that a contradiction of the nature of the medium?

Ken Burns: That’s a good question. I think that you ensure a future by having a past. If you have a past, you’re forced in some way to deal with the present in a way that you don’t normally do. So I would suggest yes. I think we’re sort of misled—we believe that our past is some very straight line that we’ve come from, and that we arrive at this moment with an almost infinitely possible future. But I would suggest that the opposite is true—that our past is a set of choices so radical that they funnel us into this moment, and that our future is more predictable as a result of the million separate ways not only that we went, but that we did not go.

I realized a few years ago that I was making the same film over and over again. Each of my films asks the same deceptively simple question: Who are we? Who are we Americans as a people? What does an investigation into the past tell us about who we have been, in order to have become who we are?

I have been making this film on Lewis and Clark, which is coming out in November, and it’s a very, very important story. We’ve chosen to throw everything into it—not just the heroic and triumphant leap ahead of time—as Americans see their own future by taking an inventory both physical and spiritual of their continent—but more individual questions and tragedies: the encounters with Native Americans and the bittersweet result of their, for the most part, open arms policy towards Lewis and Clark; Lewis and Clark’s remarkable, indeed unique, friendship, ending with a rather shocking tragedy.

As a story, it’s got everything. Clark brings along an African slave who he has had since childhood, which provides the expedition with a constant reminder of America’s tragic flaw. In their moments of greatest need, the expedition is saved by women. It’s a terrific, non-stop adventure. They fire their guns in anger only once, and lose only one member out of nearly forty-eight over the course of two and a half years in the most rugged and dangerous territory imaginable.

Making the film, I traveled through Big Sandy, Montana in Chouteau County. Chouteau County is three times bigger than Rhode Island, and has five thousand plus souls in it. I’m driving along in my Chevy Suburban through this amazing landscape, and I’m going seventy miles an hour, I’ve got seventy miles to go to the next town, and I am just dwarfed by the land. I thought about Lewis and Clark inching their way up the river at three miles an hour and I realized that although my original question had been “Who are we?”, out here the sheer size of the landscape brings you to a startling question about yourself.

I realized that traditional American religious experiment—the Shakers, the Mormons—thrived on the frontier. That, paradoxically, the time when the question of the physical survival was the loudest was also when the question of the soul’s survival was the loudest.

At that moment I realized that I had deceived myself: my question was not “Who are we?” but “who am I?” It was wonderful, because at that moment the question went out and down the valley, down to the bridge, over the Missouri and it echoed through the canyons and it stole back, very quietly, into the car where we were and settled once again as “Who are we?” For a brief moment, the question “Who are we?” had united with every individual American’s question of “Who am I?”.

Molly De Shong: In asking “Who are we?” have you come to a distinctly American answer or to something more universal?

Ken Burns: I think we discover very quickly that it’s not the answer that’s important, it’s the asking. The question is absolutely the most important thing and we deepen the pursuit by continuing to ask it. It is the province of journalism that wants the question answered, and the province of history, and perhaps better sciences, that wants the question sounded and can tolerate only an echo back. When you say “Who am I?” out loud in the West, you get, “Who am I? who am I? who am I?” And that tells you something. First of all, it tells you how far it is to the next cliff, which is very important information. It tells that you’re alone, and that’s a beginning.

But if you want to get specific, there is a set of conditions shared by those people who have somehow agreed to be Americans. But it’s the shape and contour of something that’s constantly changing, so the second you say “Aha!” it’s gone.

It is a big broad tent that we are under. There are very few, if any, other countries in the world who have agreed to come together not by geography, not by religion, not by color of the skin. For better and ill, Americans agreed to subscribe to four pieces of parchment paper written at the end of the eighteenth century, and there are constitutional diseases and strengths, belligerences and tolerances, that are inherited from that.

I’ve primarily focused on race in my work, and found the excruciatingly painful irony that the man who penned our national catechism, Thomas Jefferson, who could for the first time in human history articulate for a people its creed—”We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal”—could write those words while owning other human beings. Not once in his lifetime could he so experience that contradiction and irony that he would see fit to free them. That set the American experiment off in a tragic way in which race has become a fault line, and I have, like a seismologist, like an emotional archeologist, worked the ground near that fault line.

Molly De Shong: Unlike others, African-Americans didn’t originally choose to be a part of America…

Ken Burns: However, the great irony, the great wonderful fly in the ointment that the universe has sent at us, is the powerful lesson that African-Americans are the center of American life. I’m working on a massive history of jazz right now. Jazz is an utterly American form, an utterly African-American reaction to the excruciating irony of slavery in the midst of human freedom, which has not only provided us with so much tragedy but with so much possibility for redemption. Isn’t it unbelievable that the only indigenous American art form is created by people who, having had the ironic experience of being unfree in a free land, end up reflecting more of the American promise while having not experienced it.

So our political failures have paved the way for us, if we care to listen, to a message from African-Americans, who did not ask to be Americans in the one country that was formed by assent. But nonetheless they have shown us the way not only towards our own future but towards redemption for the crimes that permitted this injustice against them to happen.

If you see it this way, then you’ve got a different dynamic: you’re neither Democrat nor Republican, yes or no, light or darkness. You’re stepping back and you’re seeing the magical gift of having both. That we are not by accident the greatest country on Earth, but by the strange combination of faults and strengths. You know, we’re in a culture that feels it lacks heroes, forgetting that for thousands of years the message from the Greeks and the Romans has been that heroism is not the apprehension of perfection in somebody, but the extremely interesting negotiation between a person’s strengths and weaknesses. How they negotiate that is indeed what makes heroics, and what draws us to them are their flaws as well as their strengths.

So what makes the experiment of the United States, indeed the experiment of any human life, worth observing is the fact that we observe neither perfection nor venality, but a strange set of negotiations, in much the same way that jazz is a set of negotiations.

It’s too easy, too facile, too cynical, to demand that it all be perfect. I think cynicism is nothing, it’s nothing, and absolutely bankrupt. Cynicism says, “Aha—you guys think you’ve started with good will towards others, but aha! Your founder didn’t believe in it fully!”

If you stop there, that’s cynicism. But if you continue, you realize that Jefferson, having that startling contradiction, nevertheless provided the antidote to the disease that he helped to perpetuate by giving us words so vague that each succeeding generation of Americans have struggled to enlarge their meaning—first to black men, then to natives, then to women, then to immigrants, then to the handicapped, then to people of different sexual orientation.

The story of America has been taking Thomas Jefferson’s admittedly myopic phrase and turning it into a blueprint for human liberation. That’s the ultimate joke—that Thomas Jefferson may have helped to perpetuate the disease of racism that has afflicted humankind, but he also provided the antidote, in fact the cure. It’s how you see it: if you choose to see only the positive then you’ve missed the very obvious dark, but if you’ve only seen the dark then you’ve missed the redemptive possibilities.

Let me make this clear—Thomas Jefferson is the man of the millenium. He is the most important human being born in the last five hundred years, in terms of the body politic of our world. When those students were coming up against the tanks in Tienanmen Square, they were holding up copies of the most powerful weapon on Earth, which is his Declaration of Independence. His own shortcomings and failings are transcended by the effect that immortal document has had in the world. To make them equal, to say that his ownership of slavery cancels out the Declaration of Independence, is cynical. To understand them both is liberation.

Mark Gerzon: I want to return to your term “emotional archeology.” You say some of the most psychologically insightful things in your films and that makes me aware of the failure of psychology to illumine. Psychology often pathologizes, while I find that you don’t pathologize the American experience but illuminate it. What do you have to say about psychology?

Ken Burns: Nothing critical, other than to say that what you perceive might be based on the inevitable didacticism that any scholarly discipline must inevitably hew to. Why we’re drawn to art, to alternative or distant religious practices, is that while they seem to share much common ground with psychology, they eschew the didacticism that often takes years to arrive at the obvious and instead leap right into the moment. I think we would all agree that didacticism in any form denies you the experience of the moment.

Our richest experience comes from the experience of the moment, provoked by art, by another human being, or through our own discipline. I think this is the message of William Segal in both films that I’ve made with him. In the middle of “Vezelay” we’re watching a high Mass and he says, “you know, ritual is everywhere, it’s in drinking my morning coffee.” It’s almost blasphemous to interrupt that Mass to say, hey, I can get the same thing with my morning coffee, but it’s true.

Mark Gerzon: Your work illumines things I studied with Erik Erickson. There’s a way you use history to illumine the psyche, looking through the camera with an open mind at real life and trying to gain insight from it, as opposed to coming with some kind of psychological theory and applying it to everything you see.

Ken Burns: I think you’re right. If you come with a fixed theory, then you can always find the evidence or the refutation of that theory. If you’re open then you come to something else. It’s always safer to have a theory to fall back on; it’s a little bit scarier to actually be there.

I think that the success of my films comes from their being an honest recapitulation of my investigation, free of dogma. A willingness to allow the viewers to make their own connections. It’s an open framework, a process of discovery, rather than an expression of an already arrived-at end. When I’m working filming archives, it is most important for me to listen to the old photographs, because I believe they are as close a representation as we can get of that past moment. My entire desire is to do everything I can to make the moment come alive so that I will provide the audience with a potential experience of something that’s long gone, in order to make their own conclusion.

I have the best job in the world—it educates all of my parts. That’s why I don’t necessarily spend each day pursuing the spiritual dimension per se. I know that if you work humbly…that’s the word…just do your work, these things will come in.

Mark Gerzon: When I was making a film about Congress, the Speaker would not give our filmmaking crew permission for any new shooting within the chamber of the House. They said they did not want the chamber used in any way that might not reflect well on it. I almost felt that it was an inadvertent acknowledgement of the sacredness of the image.

Ken Burns: That’s right. These are the “high priests” of the religion and they were protecting the temple. They gave me incredible access when I made my history of the Congress, but it was as if I were one of them, that they felt I understood enough about the dynamic that I was an initiate. They could see whatever gleam was in my eye, but they never let me forget that this was rare access and that it was never going to happen again.

Mark Gerzon: I want to draw you out on that, because in a Christian symbology the image is sacred—Thou shalt have no graven images before thee. But now in a mass commercial market, the image is not only not sacred, it is often used to distort an opponent’s position or to sell products that hurt and kill.

Ken Burns: That’s very common and understandable, but once again, we don’t want to get stuck on the surface and get distracted by a sort of facile “Aha, caught you” attitude. The much more important thing is that we have a government that works on a classic system of the universe, right? We have a government that’s a three part government, in which you have an executive proposing and a legislative deposing—kind of an active and a passive force—and then creating a new active force, which might be reconciled by a court system. This is the Holy Trinity of American life and these people are the high priests.

In fact, in American mass culture, the Capitol dome is the most recognizable house in America, so it’s been cheapened, it’s been diminished, just as a cross has, just as the works and the words of Jesus Christ have been diminished, and crimes committed in their name.

Nonetheless, however unaware the high priests might be through the calcification that takes place in any system over many, many years, there’s a sense that something has to remain safe and true. I think it’s a supreme act of will on their part to insist on this, in the face of dollars being waved by Hollywood far beyond what a poor documentary maker could offer. Politicians who have been so simplistically maligned have nonetheless held on to something that is sacred, and this is an indication that some pure or potentially redemptive element is still there.

I prefer to see my country’s history with an unvarnished eye, an unjaundiced eye. One that accepts the tragedy, the complexity, and controversy. One that knows the point is not the simplistic, “Aha, I found you, you villain,” but realizes there might be some larger purpose served by a deeper and more satisfying study.

This “emotional archeology” has no purpose if it is to just paint villains and heroes; it has to be a whole complex picture. So I see an affirmation of what my work is about in this very guarding of the temple you discuss.

Mark Gerzon: So do I. When I raised this question, I did it in part to acknowledge them for having said, despite all the partisanship, that something is sacred.

Ken Burns: Although I think that those who are aware realize that partisanship is exactly what it’s about. I mean, the universe runs on light and darkness, good and evil, yes and no.

Mark Gerzon: “E pluribus unum.”

Ken Burns: Exactly. These people are in that tension and we know the by-product is something else again. One of the highest compliments we can pay something is that it’s greater than the sum of the parts. My life is looking for the radiation, the free electrons given off by the collision between things. So when we salute something by saying it is greater than the sum of its parts, we’re looking for what is given off through the inevitable mechanics of the universe—an active force hitting a passive force, and producing yet a third thing. We seek a kind of reconciliation.

Mark Gerzon: To me that is where the old-fashioned concept of patriotism, or love of country, comes in. We have all these diverse, conflicting, partisan parts who still share this thing called love of country.

Ken Burns: That’s exactly what it is. And it is in the American environment—filled with glaring, obvious flaws which other places have already taken care of with such smug satisfaction—where the energy is the greatest, where the possibilities are the greatest. Because America is not nearly all white and Catholic as France is, not all neat and homogeneous. It’s heterogeneous, it’s big, it’s scary, it’s moving, and that’s exciting to me.

Mark Gerzon: My favorite data on that is when Americans are asked, are they very, somewhat, or not very patriotic, 66% say “Oh, I’m very patriotic.” Then you ask them, do you think Americans are more or less patriotic than they used to be, and 75% say “Oh, Americans are less patriotic then they were a generation ago.” So what they really mean is, “I am patriotic but they’re not; what I’m doing is in the best interests of the country, but those people aren’t.”

Ken Burns: This has been going on since the beginning of the Republic. Henry Adams said, “There are grave doubts at the hugeness of the land and whether one government can comprehend the whole.” That was the great anxiety and we still have it—can one people comprehend the whole? And we have a relentless media that tells us how we don’t participate, how we’re all fractured, how every black person’s out to kill you, but in our own lives there’s no evidence that this is true. So we have a split personality.

Mark Gerzon: If I could end where we began, I see your work as a wonderful meeting place for people who think the other people aren’t patriotic. They watch “The Civil War” and “Baseball” and they say, “I’m like that, that’s me,” and they rediscover their love of this country.

Ken Burns: And they say, “That’s us.” Of course, “E pluribus unum” is exactly it. There’ll always be a tension between the two, between the one and the many, and you want that. In fact, I love the dichotomy. Look at the most maligned group in the history of the United States, which is the House of Representatives. People say, “They’re all a bunch of crooks, throw ‘em in jail, politicians are useless.” But then you ask them, what about your own Representative? And they say, “Oh, well he’s okay, he’s great.” So people actually think that their own politician is doing a good job, but it’s all the others.

I think we too often make choices based on the safety of cynicism, and what we’re lead to is a life not fully lived. Cynicism is fear, and it’s worse than fear—it’s an active disengagement. It says, “I don’t have to ask a question.” I understand where this comes from, I battle with cynicism in myself on a daily basis and there are times when it wins, and it makes you sick. I just believe that there is a better, healthier way, and for me, history is the medicine.