Three HIV-positive residents of Issan House, part of the “Greyston Mandala” of Buddhism-inspired social-service organizations, share their stories with photographer, author, and Zen practitioner A. Jesse Jiryu Davis.

A few weeks ago I visited Issan House, a supportive housing facility for HIV-positive poor people, an hour north of New York City. The facility was founded in the 1990s by Zen teacher Bernie Glassman as one of several social-service organizations in the area, collectively called the Greyston Mandala.

I photographed and interviewed three men: Darvin Edwards and Cole Preston, who are current residents, and Arthur Davis, who is a former resident and now a social worker employed by the facility. Each of these men has confronted great difficulties and spoke to me frankly. I intend to represent them here in the same spirit of respect and love as Bernie Glassman had when he founded Issan House. I hope you read their stories with this intention, too, and find your own ways to amplify the voices of people who are too rarely heard.

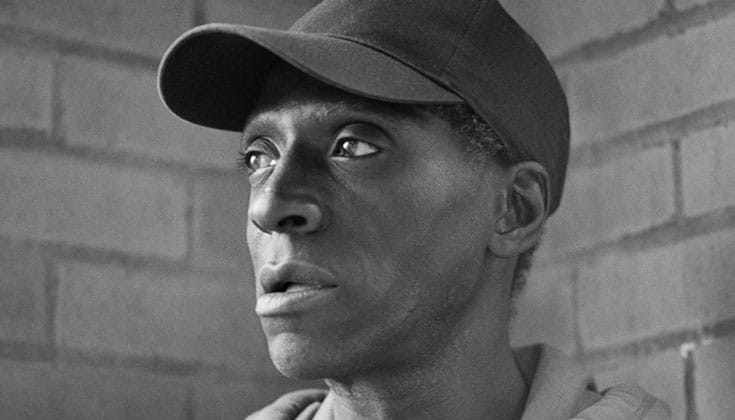

Arthur Davis

I didn’t know I had the virus. I’d been tested in the past, and I was always negative. But there was a telltale sign: I could not stand the light. It felt like it was piercing through my brain. I had to keep something over my head so no light could get in. I don’t know how long I was like that, I lost all perception of time. I wasn’t working or doing anything, except for avoiding the light like a vampire. Lo and behold, meningitis.

One day in 2001, I passed out. I had gotten up to put a plate of food in the microwave and then I woke up on the floor. In the hospital they said, “We’ve got good news and bad news.” I’ll never forget it. They told me the bad news: I have HIV. I said, “So, what’s the good news?” “Well, now you can apply for welfare and they’ll pay your bill.” I said, “Get the fuck out of my room.”

When I moved here, to Issan House, I couldn’t walk, I had to hold onto the walls. I figured I was going to die. But since I was stuck here anyway, I started taking the program next door, learning about the virus. I learned that you can live.

The most satisfying thing is when someone says, “Thank you.”

I learned to advocate not only for myself but for others. That’s when I started doing outreach. I wanted to see everybody do better. Talking to the community that wasn’t infected, passing out condoms. I took these little steps, and I became indispensable. I taught every new staff person who came in how to do their job. Now I’m a medical case manager.

You feel safe in this place because everyone has the virus. I don’t have to blurt out that I have it. Every now and then someone moves in and says, “You don’t know what I’m going through.” I think, you’d be surprised at what I know.

Sometimes people don’t follow the rules, they get evicted and end up at the shelter. I used to bring them stuff to eat, but I stopped that—I know I can’t save the world. They have to learn to save themselves.

The most satisfying thing is when someone says, “Thank you.” It’s not too often. Or when someone comes back to say, “If it wasn’t for you, I don’t know where I’d be.” That’s happened once or twice.

I act like I don’t care, but I do.

Cole Preston

One time, I just got off work, I met this lady on 241st Street. She was out there tricking, you know, she was a prostitute. We was going to do that. I threw my bike in the back of her car and she took me home. But her conversation was so good, by the time we got home, I never got the chance to do that. “Let’s just get high, because you’re beautiful people,” I said. “We’re going to get high, we’re going to talk.” Her name was Ebony. She told me she was sick. I thought I was probably sick too. She died. She was someone I truly loved.

When my parents split they abandoned their house in Mount Vernon. So, I opened it back up. I cleaned it up. It didn’t have no lights, but I did everything to it. I rented out the bedrooms on the second floor, like a little whore house. I stayed downstairs in the living room, smoked my crack and monitored everything. I was making money, you know, for girls to bring tricks in there. Then the place got raided and I went to jail.

When I got out, I was in the shelter and they test your blood. They said there was something in my blood, I need to go get that checked out. For years, I was thinking I was sick anyway: “I can’t be, but I gotta be.” Maybe from Ebony, maybe from some other girl. My mom was with me when I got the news, because my mom has always been in my corner. I had to tell the lady friends that I’d been with that I had the virus—by the grace of God, none of them is sick.

Today, I live for me. This place is home for me now.

When I found out I had HIV, I told my mother that I didn’t want to take medicine. I felt like, “Why? I’m going die anyway.” My mother said some good motherly words. “Just take it for me. Live for me.” And I said, “Okay. I’ll do it.”

My mother found out about this place, Issan House, she brought me here and she paid the rent the first year. They took care of me here for the first 8 years, then the last 3 years, I grew up. I don’t need them to take care of me no more. Today, I live for me. This place is home for me now. I got my bike here and my family pictures. I got my father here, he was in the military, he loved to dress up and put on all this stuff.

I never had a car of my own. I was born with bad eyesight. Then this February, I was talking with a friend that used drugs. I wouldn’t buy her no more drugs, we got into a little something. She poked me in the eye, broke my retina. I don’t think I’ll get a driver’s license with my eyes the way they are right now. So, there goes the Lincoln. But I can get me a girl with a Lincoln!

Darvin Edwards

Mostly, before I got here, I was on the street and homeless, hungry and stuff. For a while I was in a rehabilitation center in the Bronx, then after that I moved to a home for adults in New Rochelle. They didn’t serve me good there. There would be a lot of fights. But they did help me come in here. Issan House considered me because I was an HIV person.

It was a transfer from a girl with a penis, to me. She didn’t tell me she had HIV or nothing like that. That’s how I caught it. I think she should have told me about the problem she had and how it would affect me.

Now I’m living by myself here. It’s alright but I’m missing home. My mother told me I have to be independent and look out for myself. I don’t want to take anything from her. When I was young she was very poor and didn’t have nothing. She wasn’t getting enough to feed the family. I talk with her all the time, though—I’ll call her tomorrow and tell her, “Happy Mother’s Day.” I haven’t seen my father in a while. I tried to call him several times and he didn’t answer. He’s still the same and I’d normally get a beating, so I’m not going to call him.

I have to go back and forth to the hospital rehabilitation center, it’s very cold in there, but they say the medicine works better when it’s cold. This HIV is going to hold me down. I’m not going to try to get any good jobs because they think it’s going to spread and stuff like that. I have dry skin and if I come to work and they see that, they see it’s ashy and they won’t give me a job. It doesn’t make me angry. Sometimes I’m struggling, but a lot of people here help out. As long as l’ve got a roof over my head, then I’m alright. I’ve got friends here.