John Malkin talks to musician Jarboe about the influence of Buddhism in her work.

Jarboe. Photo by Marilyn Chen.

Jarboe is an American vocalist, multi-instrumentalist, and artist who lives near Atlanta, Georgia. She was a singer in the rock band Swans, has collaborated with other bands — including Neurosis — and has produced many solo albums. Her music can be considered a blend of melodic gothic, extreme metal, modern tribal, and experimental opera. Jarboe’s solo projects and musical collaborations have often been grounded in a spiritual, internal exploration.

Jarboe’s latest album, Cut of the Warrior, was released on December 14, 2018 by Translation Loss Records and is based on Tibetan Buddhist practices like tonglen — a method of empathetically exchanging self for others — and chod — a practice for confronting attachment to ego and the body. Chod practice was developed by the 11th-century Tibetan yogini Machig Labdrön.

From an early age, Jarboe’s father encouraged her to sing and play organ, and she thrived musically. Later, her father was less enthusiastic when Jarboe decided to trade in traditional opera and choir vocals for rock and roll. Today, after some eight Swans albums, twelve solo albums, and multiple collaborations over thirty-five years, Jarboe continues to create music as a truly independent and thoughtful artist.

John Malkin: Tell me about your interest in Buddhism.

Jarboe: I’ve been studying Buddhism for many years. My interest came forth in Swans as well as my solo work. I was in New York during the International Year of Tibet [1991], and the Dalai Lama was at Madison Square Garden and the Paramount Theatre, delivering the Kalachakra Empowerment. I participated in that and it was a very interesting process. We were instructed to walk there, if possible. It was great. I’d get up at dawn and walk the sidewalk from the East Village all the way up to Madison Square Garden. I’d see the monks on the sidewalk doing the same — walking — and it was that whole ritualistic aspect of starting in the morning to get there that really set the tone for the day. It was a fascinating experience.

A lot of events during that time aligned with things I’d studied and thought about my whole life. A lot of it had to do with the fact that emotions are not real; they’re a chemical state that comes and goes. So, rather than being afraid of them, you can embrace them, because they’re going to be leaving the same way they came in. So, you’re not a slave to your emotions. That’s what opened up the door to all of my lyrics.

Once I had this revelation about emotions, I let go of writing torch songs about pain and men and heartbreak and romance. I wasn’t interested in that anymore. I found something that rang true: trying to deliver a message about what I was studying, which was that these emotions are temporary states.

On the tour that I’ve been on for over a year now, throughout Europe, Australia, and the West Coast, we end with the song “Nothing Is Here to Stay.” The lyric “Nothing is here to stay” repeats in a mantra-way, but in a child-like voice that I use. “Pain is not punishment / pleasure is not reward / nothing is here to stay.”

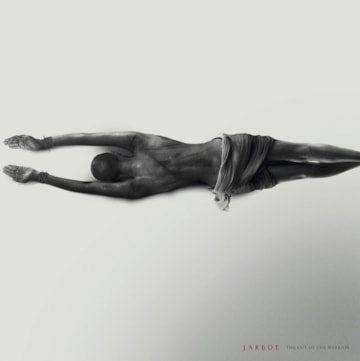

Tell me about the album cover.

Tell me about the album cover.

For Cut of the Warrior, she is illustrated with cuts on her body. The state of chod is the “cut of the warrior.” She is shedding the ego in a literal manifestation of the metaphor of chod; the warrior attempting to cut the ego.

On the Buddhist path, there are many secret rituals. A lot of them have been lost through time, but the basic gist involves the tantric feast. There’s a song called “Feast,” and she’s in that piece having visions. In my interpretation it’s a visualization rather than actual cuts to the body or sexual ritual. The feast is a visualization.

One of the new songs is titled “Karuna.”

Karuna, in the Buddhist interpretation, is compassion. I’ve been addressing the issue of compassion for a couple of years now, with things I saw happening in the United States. When I reacted deliberately, that resulted in the album “As Mind Dissolves, As Song Begins” [2017]. That is an interpretation of a line from Rumi. I was studying Rumi, and at the same time I was looking at these political rallies of the person who is in the white house right now. The juxtaposition of the divine laws and what I saw as shear hate really hit me hard. And that’s what gave birth to that.

I deliberately did an album of vitriol and anger and used rock instrumentation to manifest that, and then on the opposite side I used songs about divine love. This is to show the contrast. And I ended it with something called “The Rally,” which has a recording I made secretly at a rally. I used some chanting that happened at that rally and I processed it and put it into the mix. It’s rather chilling, especially for people that understand exactly whose rally I was talking about [laugh]. So, this set the tone for more intense discussions about compassion.

Karuna was recorded in a dome and there’s a lot of clanging metal in it. It’s an actual session of [Tibetan Buddhist] meditation. There’s a line, “If you call her, she will come.” This is about calling on compassion.

It’s sounds like you’re engaged simultaneously in finding something to do with anger and being compassionate. And facing the reality of impermanence while not denying that there’s social injustice going on. I think some people tend to choose between a spiritual practice and taking action in the world. I’m always inspired by people who do both fully.

I think it’s important. The only way things can change and evolve is to take action and get involved. Whether it means going door-to-door or going to a march. At the same time, I am acutely aware of the fact that people don’t want to be preached to, so what I do is gently offer my own views, and if someone respects or cares about what I have to say, here it is. But I’m not going to go on a tirade, because people are getting enough of that as it is!