Jill S. Schneiderman on why Buddhists need to put their foot down and stand up to oil companies’ destruction of the environment.

“What counts is not the enormity of the task, but the size of the courage,” says Matthieu Ricard, a Buddhist monk and confidant of the Dalai Lama who was dubbed “Mr. Happy” after U.S. neuroscientists declared him the most content man they ever tested. Ricard’s statement resonated for me in light of continued developments in what I’ve come to think of as the Earth Day BP Oil Catastrophe. We’re going to need this kind of inspiration in order to deal with the Gulf of Mexico mess because the magnitude of the task before us—stopping the forcefully gushing oil, cleaning up devastated habitat, caring for injured or soon-to-be-harmed living beings in the path of the petroleum, protecting as yet unaffected regions—boggles the mind as it stirs the heart.

Since I’ve just returned from a weeklong Jewish Mindfulness Meditation Teacher Training retreat, I’ve been away from the news of this calamity. But sad to say, my geologist’s perspective leaves me unsurprised by broadcasts of impotent efforts of oil industry professionals to handle the tragedy. Why? Because I’ve been sitting for the last week paying attention to body sensations, I’ll just say that we earth scientists feel in our guts the vast scales of Earth time and space; (it’s why I write about them). As Congress and a federal panel in Louisiana begin their inquiry into the situation not one person should be perplexed by the sequence of events that follow the explosion and sinking of the Deepwater Horizon oilrig. Here’s why.

First of all, this event is much more than just another “oil spill.” To me, the word spill suggests flow from a confined space and implies a finite amount of liquid. The monster in the Gulf of Mexico is a gusher, a blowout, an uncontrolled flow of oil from a well bored into the earth, what drillers call a “wild well.” Dr. Frankenstein has put a spigot in the Earth and can’t shut it off.

When in September 2009 BP announced its discovery of the Tiber oilfield—what the workers on the Deepwater Horizon were boring into when it exploded—they characterized it as “giant” and meant to convey that their find contained between four and six billion barrels of oil; this contrasts with a “huge” oilfield usually considered to contain 250 million barrels of the stuff. Regardless of whether it’s giant or huge, this Gulf of Mexico event is more than a spill. Basically we’ve tapped into a source of oil that will not be exhausted quickly. Isn’t that ironic?

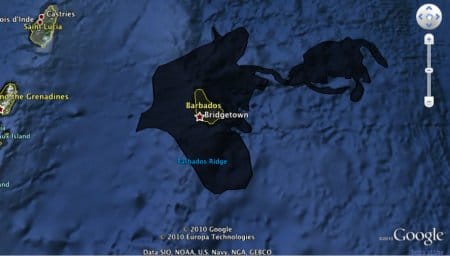

It’s impossible to conceptualize such vast quantities, and as the crude oil continues to spew for the 24th consecutive day at daily rates reported to be 210,000 gallons, I’d like to help. Check out a Google Earth map website by Paul Rademacher that will allow you to compare the horizontal extent of the oil with the geographic size of your city, county or state. I checked Barbados, the tiny island on which I currently live; the crude oil would blanket it completely.

Ditto my home county—Dutchess in New York. It’s way bigger than Rhode Island, our convenient measuring rod for environmental disaster (Remember the Larsen Ice Shelf? The 220 meter thick—three football fields—chunk of ice “the size of Rhode Island” that disintegrated in 2002 after having been stable for up to 12,000 years.) Check the places that matter most to you and sense in your gut the feeling caused by the spatial comparison.

And speaking of space, oil and gas executives crowed about their record-setting achievement, touting it as one of the deepest wells ever achieved by their industry—drilled 35,055 feet deep into the Earth’s crust beneath 4,132 feet of water. You may wonder, “Just how deep into the earth is that?” Let’s put it this way, transcontinental flights cruise at that elevation above the Earth’s surface. Next time you are in an airplane, picture a pipe connecting your jet to the surface of the Earth and you’ll have a picture of the distance that BP went to access the Tiber Oilfield black gold.

Would that these innovators had gone to such extremes in order to apply to their work an ethical code that includes the Precautionary Principle:

“When an activity raises threats of harm to the environment or human health, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.”

Regrettably, precautionary action has been the exception rather than the rule in U.S. environmental policy. Perhaps it has operated to the frustration of some in decisions concerning disposal of high-level radioactive waste at Yucca Mountain, but the Earth Day BP Oil Catastrophe demonstrates the virtue of Vorsorgeprinzip, German for “precautionary principle.” Literally, Vorsorge means “forecaring” and conveys forethought and preparedness—not simply “caution.” I say that a plan to bore “the deepest well ever” into the Earth, should be accompanied by accurately scaled and well-tested models for responding to unexpected contingencies. Ahimsa, first do no harm.

The first homework assignment of my Jewish Mindfulness Teacher Training program was to read Jack Kornfield on the five basic Buddhist training precepts. Number two, “we undertake the precept of refraining from taking that which is not given,” strikes me as particularly apt given the circumstances in the Gulf. We consent to not take that which does not belong to us. We agree to bring consciousness to the use of all of the earth’s resources in a respectful and ecological way.

When will we, like Job, clap our hands to our mouths with the realization that human beings occupy an infinitesimal place within a divine whole? When will the “knowledge” of modernity succumb to the wisdom of the ancients? Could the answer to Job’s question of how long must his people suffer, “Till towns lie waste without inhabitants, and houses without people; and the ground lies waste and desolate (Isaiah 6:11),” be also the answer to the question, when will the oil stop gushing? The chutzpah of humans got us into this mess; humility will help us out of it. We will need clear mind, wise heart, and sizable courage to say dayenu, enough.