In the world of fashion, there is no old age, sickness, and death. In the world of fashion, we are always young, beautiful, and of the moment. Otto von Busch breaks down the mass marketing of denial.

The story goes that before becoming enlightened, the Buddha was a young noble in ancient India, free from suffering in his palace, indulging in all kinds of princely pleasures, adorned in gilded dreams. But one day, as he ventured out from the palace gates, he confronted the unavoidable truths of existence: a sick person, an old person, and a corpse. For all his years, the young prince had managed to deny the fate of all life—sickness, aging, and death—and the encounters became messengers to the young prince.

This well-known story reveals how the untrained mind is in a continuous denial of our approaching demise. Our mind keeps itself busy and is always hunting pleasure in order to dismiss that we will all eventually get sick or experience disease, that it is a natural and unavoidable process that we age, and that everybody dies.

We feel that fashion can give us what we need. We can be beautiful. We can be seen. We can be popular. We can become a better self. And it is so accessible. It is everywhere.

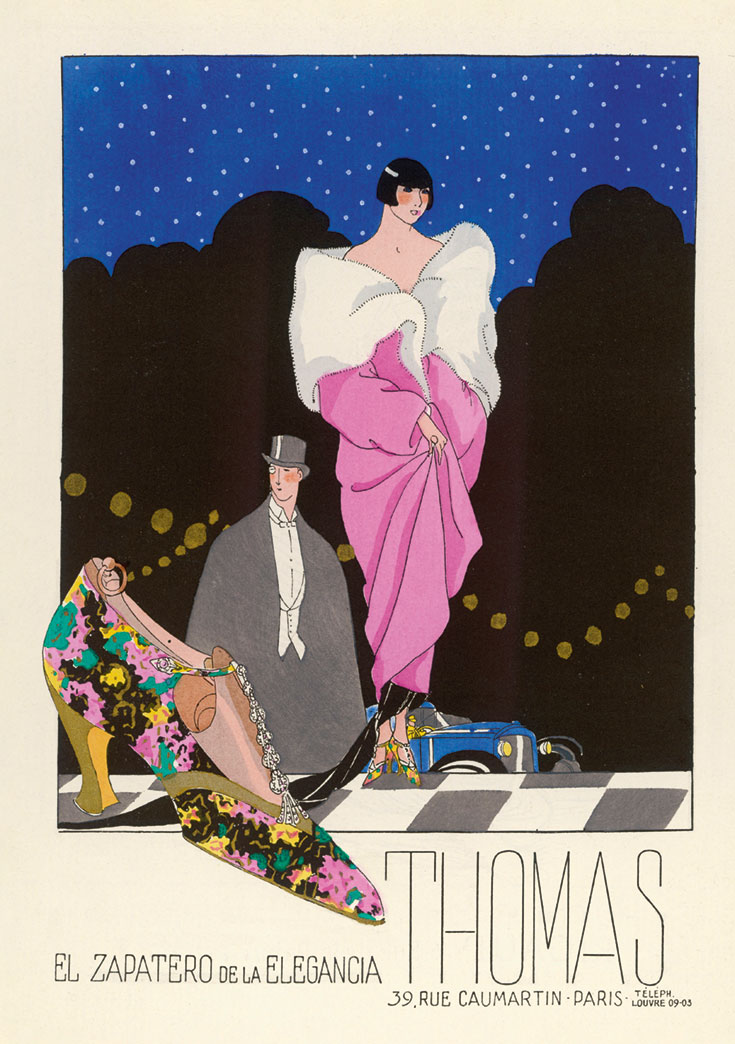

Fashion sells us the cure—or at least a Band-Aid. It veils existence in seductive and ephemeral allure, effectively hiding these inescapable facts from our attention.

There is no sickness in fashion, only ideal healthy bodies of radiant complexion. There is no aging or sagging skin, only an ever-recurrent celebration of eternal youth. And there is no death, only the continuous flow of new seasons and collections. The sales are quickly over, and garments that no longer spark joy are doomed to the shallow graves of the dump or sent to the incinerators of sentimental values.

It is no wonder we look to fashion for alleviation. We feel that fashion can give us what we need. We can be beautiful. We can be seen. We can be popular. We can become a better self. And it is so accessible. It is everywhere.

On top of that, fashion sells me an ephemeral sense of freedom, and with each new purchase a fresh wind blows into the wardrobe. Yet my mind is stuck, as if in a continuous loop: “Am I good enough?” “Will I pass?” “How do I get more?” I close myself into an ego-centered loop of aversion and denial, clinging to the passions of consuming youth.

Even if we don’t care about clothes, others do; we are doomed to appear before others. By appearing before others, we put ourselves up for aesthetic assessment. Even if we don’t judge others by their looks, others will judge us. Even if we never change our clothes, they still speak of some relation to the fashion of our time. It can be both a blessing and a curse. It can offer a sense of aliveness and attention, a thrill of being seen, acknowledged, and attractive. But it may also put us up for painful conditions of anxiety, overload, and addiction.

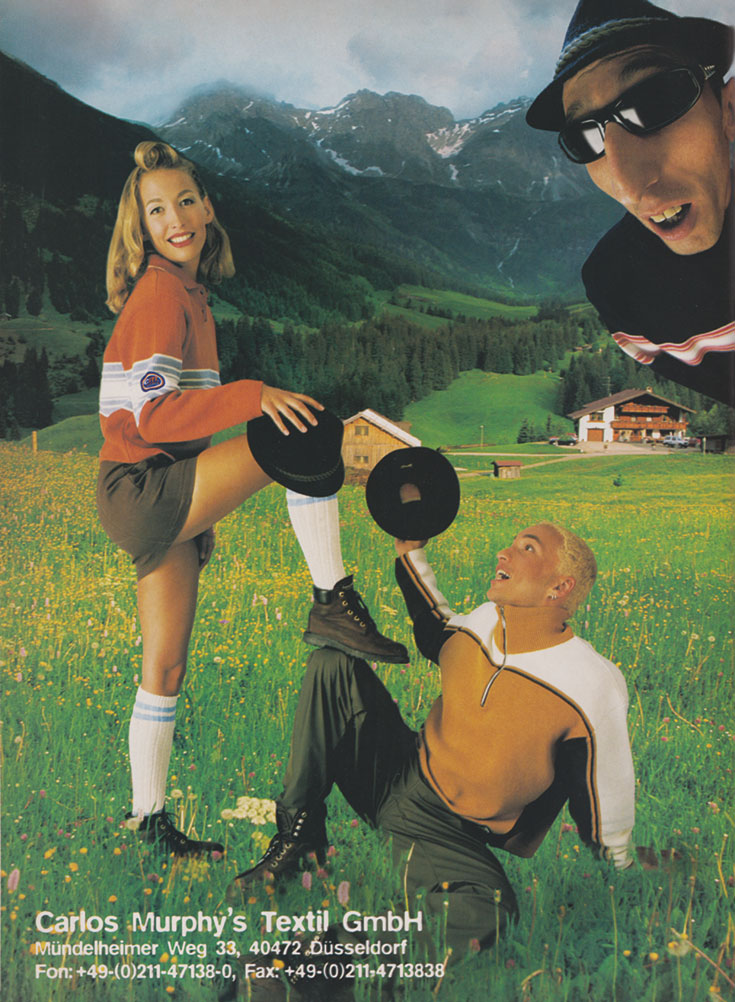

We crave pleasure and are averse to pain. We are restless. And we all want more. When we leave the fashion boutiques with just the right new things, we beam with pleasure and life. Feeling inches taller than before, we need shades to look into our bright future.

Today, the processes of fashion extend to broader and broader spheres of collective life. Everyone is more or less immersed in fashion, more or less everywhere. As cultural theorist Gilles Lipovetsky posits, fashion sells an image of independence—an ego that is more fully in charge of itself. And even more, fashion sells us the experience of freedom. Paired with youth, status, and belonging, fashion is, by definition, always the right thing to wear in a certain time. It is always the right thing to do.

It may be a sign of our times that our primary sense of agency and power comes packaged in goods. To most people submerged in the consumer economy, the most powerful sense of affecting one’s life is based on what to purchase. Most of us have little influence on the private governance of the workplace, and we are compensated by procuring a sense of agency at the end of the month. Fashion, like freedom, is something we buy.

Fashion arouses the ego: it makes us feel young, fresh, attractive, and free. But it cannot stop the process of dying.

In the affluent abundance of cheap clothes on trend, we can dress like our idols, gaining temporary access to the aura of celebrities and the palaces where dreams are made. Don’t fool yourself: everybody desires the pleasures that come with fashion. Even those who do not dare to dream know to love success.

Fashion is often blamed for being shallow and ephemeral. But that is its purpose. The pleasures and allures of fashion lead our attention toward the unencumbered affirmations of life. The iconic fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent is famously attributed to saying, “The most beautiful makeup of a woman is passion. But cosmetics are easier to buy.” Fashion does not substitute passion; it is an extra layer of affirmation, accessible and transformative as it conveys seduction, aesthetic delights of eternal youth, and lotus-scented oils of hedonism. Such exhilarating feeling of life—at its best, fashion is experienced as the opposite of aging.

Fashion arouses the ego: it makes us feel young, fresh, attractive, and free. But it cannot stop the process of dying.

If we are free to consume and express ourselves, yet still fettered to unhappiness and anxiety, can we really say that we are free? If we do not bring our choices and emotions to mind, are we not simply slaves to the industry, to the opinions of our peers, to our sensations, and to our indulgent habits? As pointed out by Zen priest Shohaku Okumura, we may think we are driving a car, but a more accurate way to look at it would be to see the car driving us. It is the oil economy and the global supply chains that propel the car. It is the politicians, planners, highway construction workers, and advertisers who made our habitual desires translate into continual driving, fueled by our dependencies on oil, wars, and strip malls.

The same could be said about fashion—the decisions of what I can wear are already taken, and my desires are designated, branded, and packaged for me. Yet, I still experience my taste as uniquely mine. With my purchases, I take charge of my life yet remain fully seduced by temptation and desire. But more importantly, my desires are driven by my untrained mind, my stressed and confused thoughts, my habituated delusion of being free.

Many today agree the current model of fashion is not sustainable, and even toxic to the planet. Brands sell more eco-friendly collections, recycle a bit, circulate some materials, and suggest our consumption can be more “conscious.” Yet, paradoxically, most of us remain totally unconscious about the psychological driving forces of fashion, the seductive aversion from aging, sickness, and death. It is taken for granted that the aversion, delusion, and greed that reside at the core of fashion are virtues that drive a healthy economy.

Fashion is denial, draped in expensive fabrics. No society can understand itself without looking at its dark side, and for fashion, this is the realm of denial. The same denial experienced by the young Buddha in his palace. It is a process expressed in obsessive consumerism, compulsively seeking the thrill of the newest looks, the kick of affirmation that comes with feeling seen and affirmed. The denial at the heart of fashion comes with the admiration of the ego-centered influencer.

We can speculate about what would be wiser ways to be with our dressed appearances, and try to reconcile desire with the suffering that comes with aging, sickness, and death. Can we find more-meaningful ways to be with fashion than a continual cycle of purchasing a very limited sense of freedom? If we unpack our relation to fashion we may understand our lives better. Not only that, our relationship to fashion may help offer some insight to more general aspects of our everyday lives. Can we transform habits of self-indulgence into insight?

It is said that on the eve of his enlightenment, the Buddha sat beneath a tree and was assailed by the demon Mara. Mara is literally “Death,” the personification of temptation and distraction. Using seductive images and ultimately doubt, Mara challenged the Buddha, distracting him from his goal of enlightenment. After several unsuccessful attempts, Mara retreated. By knowing and seeing Mara with unhindered attention, the Buddha could turn the demon away.

Mara is always within us. The demon represents everyday experiences, such as fear, temptation, anxiety, relationship difficulties, and addiction. These are just some of all the afflictions we meet in the landscape of our minds: restlessness and anxiety, desire and craving, aversion and delusion, and, finally, doubt. Mara urges us to avoid all the unpleasant mind states that accompany the path toward healing and awakening and instead engorge in all temptation for pleasure.

It is not foreign to draw parallels to fashion. Like fashion, Mara is what tempts us, and cannot be overcome with simple denial. Rather than applying brute force, which is useless against temptation and craving, the Buddha’s example suggests approaching Mara with the spirit of listening and transformation. Mara can be won over with weapons of compassion, equanimity, appreciation, and, ultimately, insight, in order to establish sovereignty of our own minds.

Fashion is fueled by our desires, and in many ways, we dress to become our desires. But uncontrolled desire combined with our hunger for attachment easily turns into craving. We spot an attractive friend crossing the road in just that right thing, making him or her stand out as a mirage of perfection. We may not spell it out, but the rush in the body cries “I need that too!” The look appears to us as a ticket to that world, a signature texted as a postcard from a place of allure. A low-level fever runs through my body: “I need to find that outfit!” Passion can be almost indistinguishable from a fever, so no wonder that fashion is such an incubator to that pleasant sickness of consumerism.

Not unlike how Mara bedevils the Buddha, it can be fruitful to think that fashion is not entirely chosen by us, but it assails us, is inflicted upon us. But does that necessarily mean we are “victims” or “slaves” to fashion?

The idea that consumers are subject to some forms of submission to aesthetic power may not be inaccurate. However, the framing of the relationship as master/slave may shy away from the complex social relationships that fashion and consumerism flourish in.

“I was absolute master in my old dressing gown,” philosopher Denis Diderot famously put it, “but I have become a slave to my new one,” since he felt the need to update his whole wardrobe because of one new piece. We may think we choose fashion from our free will, but with just a little bit of self-observation, we find ourselves subjected to the tastes of our peers, our habits, and our confused minds. And as with a new dressing gown, our desires creep upward, ever wanting more.

But today’s fashion consumers don’t see themselves as slaves. Instead, we are continually sold aesthetic rebellion and independence. We do not submit to fashion; we crave fashion. We celebrate impulse buying and happily engage in retail therapy. Fashion is not about subordination as much as a site for tension, anxiety release, and soothing from stress.

We shop, dress up, feel the hungry eyes of our peers, and the brain’s reward system runs on the highest levels.

And even as we cannot escape the news of environmental impact of mass consumerism, we keep shopping. Perhaps it is true, as Buddhist ecologist

Stephanie Keza argues, that we are stricken by a “sickness of consumerism,” a spiritual disease of unquenchable consumption, poisoning, and denial?

But don’t we also crave fashion because it is a little forbidden, that it flirts with danger, the gamble of the passions? Fashion is the antipode to frugality, and some shame is still bound to the blatant egotism of fully and flamboyantly celebrating one’s desires, which may still be the model of orgiastic pleasure. Indeed, isn’t fashion partly about the pleasure of challenging virtue, gluttonous delight, and a thrill in greedy jealousy, to envelope ourselves in virtuous sin, taking sartorial risk and challenging the fates? It is the kick that makes me feel more alive, if only for a short while.

We shop, dress up, feel the hungry eyes of our peers, and the brain’s reward system runs on the highest levels. As I leave the store with the new goods, I feel like a conqueror and experience the emotional kick that comes with gaining a few notches in the gamble of attention.

Through consumption, grasping generates both the safety of identity as well as the thrill of becoming renewed. As I consume, my sense of identity becomes tightly knit to my feeling states.

“Shopping is a way that we search for ourselves and our place in the world,” psychologist April Benson argues; “a lot of people conflate the search for self with the search for stuff.” As I wear sophisticated Japanese designer clothes, my whole cognition speaks to me as if I am a sophisticated person. I want to feel like a queen or king again, and I crave more. As what I acquire arouses me, I am also seduced into believing I am what I consume.

Perhaps we can find ways to deal with our cravings for the new, for the latest kick of dressed affirmation? A first step may be to start relating to fashion, rather than from fashion; to grow a sense of self-knowledge with fashion. When we are not paying attention, we let our cravings motivate our actions, whether we like it or not. By paying better attention to our emotions, we can better unpack what fashion does to us and how to respond to these emotions in a wiser way.

Even after the Buddha’s victory, Mara did not disappear. Instead, Mara continued to live with the Buddha, kept returning with new temptations and doubts. In some traditions the demon eventually becomes a disciple of the Buddha. A possible task is to make friends with our desires, our self, at the most profound level possible. The task is not to resist or deny our experiences, but willingly invite Mara. In the moment of burning desire, and with this clearly recognizing the reality of craving, we may try to open a dialogue of understanding with Mara, examining the roots of our temptations to overcome Mara’s intimidation.

Adapted from The Dharma of Fashion: A Buddhist Approach to Our Life with Clothes, by Otto von Busch and Josh Korda, illustrated by Jesse Bercowetz. Published by Schiffer Publishing (schifferbooks.com)