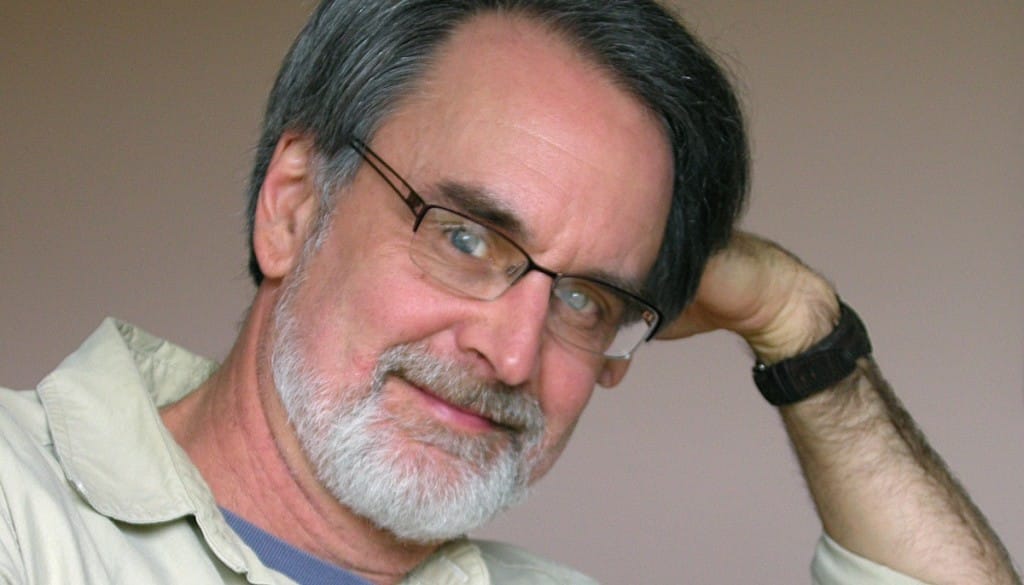

Cary Groner discovered Buddhism in high school and it immediately resonated with him. But his mother thought meditation was peculiar and forbade him to do it. “I’d get caught meditating the way that other kids get caught smoking dope or shoplifting,” says Groner, the author of Exiles. “Fortunately, meditation is something you can do without making any noise or attracting any attention, so at night I’d sneak out of bed and sit on the floor and practice.” It felt quite subversive, which made it all the more appealing.

In his twenties, Groner felt the need for a Buddhist teacher and searched for a fit. Then one day in 1985, he was in Powell’s Bookstore in Portland when he saw a poster for a talk by Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche. “In the poster, Rinpoche was laughing and had this look that was fierce and funny and profound all at once,” says Groner. “I remember thinking, this might be the guy.”

And he was.

Groner spent the next couple of years living at Chagdud Tulku’s center in Cottage Grove, Oregon. “Rinpoche was the full package,” says Groner. “He had deep insight and compassion, yet he was also totally down to earth and very funny. That’s not to say the relationship was all peaches and cream. He had quite a temper and could get wrathful. Being with him was by turns exalting and terrifying, but Rinpoche hammered away at the encrustation of habits I came in with, and I did my best to hang in with that process.”

These days, Groner is studying with Chagdud Tulku’s lineage holder, Lama Drimed Norbu. He does a retreat every summer and he’s part of a small group in the Bay Area that meets to do tsok, a Vajrayana Buddhist practice of offering and purification. From Groner’s point of view, he’s lucky. As a writer working from home, he can usually sit for a couple of hours each morning.

Groner writes in various genres. He has more than twenty years of journalism under his belt and writes often about health-care, specializing in lower-extremity biomechanics. He’s been writing plays and poetry since he was a teenager and fiction since his twenties. That said, years went by without him having much success with creative writing. “I wrote plays and couldn’t get them produced,” he tells me. “I wrote screenplays and couldn’t sell them, and I wrote a couple of really terrible novels. Finally I decided if I was going to do this, I had to stop screwing around and really bring some commitment to it.”

In 2006, Groner began his MFA in fiction writing at the University of Arizona, and his thesis eventually became Exiles, for which he landed a book deal with Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House. Exiles is the story of cardiologist Peter Scanlon, who takes a look at the rubble of his failed marriage and moves to Kathmandu to volunteer at a health clinic. Never imagining the risks and hardships he’d find there, Peter takes his seventeen-year-old daughter with him. The poverty, the child prostitution, the shortage of medical supplies, and the unfamiliar diseases are all a shock, but the encroaching civil war could cost father and daughter their very lives.

“When I started writing Exiles, I was interested in the overlap between Buddhist thought and the sciences,” says Groner. “So my idea was to write an epistolary novel, an exchange of letters between a Tibetan lama and an evolutionary biologist. But it didn’t take long to realize that would be interesting to me and about five other people on earth. If I wanted anyone to actually read the thing, I had to come up with a narrative.”

Out of this realization, Groner eventually developed a fast-paced plot, honed draft by draft. There are keys to creating suspense, he learned. Within the overarching conflicts that form the narrative’s spine, there need to be other problems that twist and turn, so that every time a character solves one problem it creates another. That way, there’s always a challenge that characters are working on. “This is very much like life,” says Groner, “like samsara.”

The action-packed storyline may have been a departure from Groner’s original idea for Exiles, but one element, at least, has remained the same: the theme of science meeting Buddhism. In the finished book, the science angle manifests as Peter, the American doctor with a background in biology, while the Buddhist angle manifests as a Tibetan lama. Peter and the lama meet in Nepal, and their conversations challenge Peter to think deeply about issues such as evolution, the mind, and the nature of existence.

“Writing from a spiritual perspective can be tricky,” says Groner. “You want to be true to your interests and experiences, but you never want to turn your work into propaganda. It’s important to remember that your job is to write, not proselytize.” Although Exiles deals with Buddhism, Groner is primarily focused on telling human stories and revealing how people are led by their foibles to some sort of crisis and then to understanding. “This,” he says, “is what all storytellers do, regardless of whether they have spiritual inclinations or not.”

Groner occasionally experiments with magical realism, but these days he does so sparingly. Despite his admiration for writers such as Gabriel García Márquez, Groner feels that, as a reader, unearthly happenings engage his skepticism and pull him out of a narrative. Magical realism, Groner says, can “distance the reader from the real human experience unfolding on the page.”

“Real” is not a word that Groner hesitates to use when describing fiction, because, for him, fiction requires relentless honesty. As he puts it: “The revision process not only involves looking at structural issues, such as information release, rhythm, and tone. It also involves relentlessly ferreting out anything dishonest in the writing, by which I mean anything that is not how things are in real life.”

Groner often hears writers claim that writing is their meditation. But in his opinion, these two activities are distinct. Writing, for him, is more like a waking dream—the writer is following the story that he or she is creating. Meditation, on the other hand, is much more open and free. Yet Groner says there is one way writing and meditation are the same, and that’s the flow they share, the way they both make you lose track of time.

“Writing and meditation are compatible,” says Groner. “Anyone who’s tried to sit quietly for periods of time knows the fantastical capabilities that get unleashed when all you’re looking for is quiet. I sometimes keep a little pad and pen with me so that if I get a good idea I can jot it down and forget about it, because otherwise I try to hang on to it and it becomes extremely distracting.