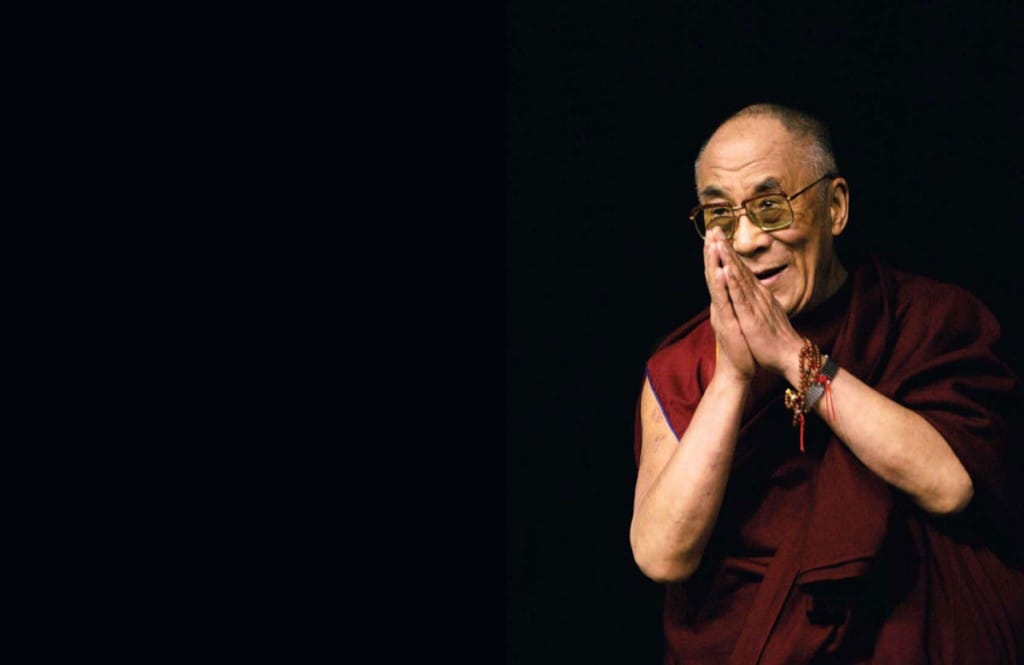

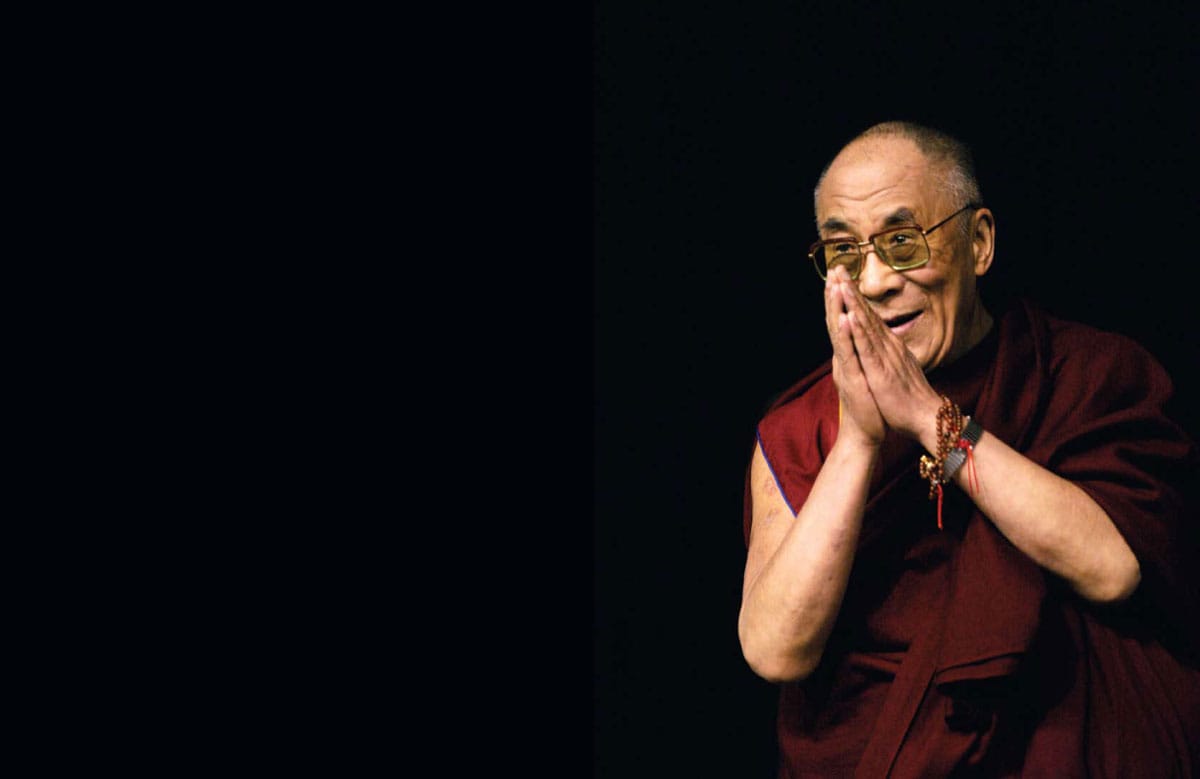

The world’s most famous “simple monk” is far from simple and more than just a monk. Barry Boyce is there as the Dalai Lama displays the many faces that make him such a unique and important figure.

It was autumn 1979. Tense times. President Jimmy Carter was reeling from stagflation, the energy crisis, and the Iranian revolution. After being rebuffed by the State Department for six years because of the “inconvenience” a visit would cause for Sino-American relations, His Holiness the Dalai Lama was finally allowed to enter the country. He began his twenty-two-city, seven-week tour of the United States with an address in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, and shortly thereafter entered the nation’s capital for the first time.

In those days, no books by the Dalai Lama filled the shelves. No Nobel Peace Prize. No White House grip and grin. No meetings with scientists. No International Campaign for Tibet. Hoary fifties-era high school geography tales of the god-king of Shangri-la preceded him. He came in on little cat’s feet. Not a god-king, he told crowds. “I am a human being,” he said, “a Buddhist monk.”

In its report on the visit, Time magazine informed its readers that “many people thirty and younger are drawn to Oriental religions that explore inner spiritual resources through meditation,” and that the Dalai Lama was “particularly interested in meeting this younger generation.” I was one of them. My Buddhist teacher had instructed his students to do what we could to help host His Holiness. Our group in Washington mustered as many people as we could to provide a form of “security” for some of his comings and goings, including a public talk at the Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall. The day His Holiness arrived, we were briefed for our upcoming duties by a private security operative hired by the Office of Tibet. He intimated that he would be “packing heat.” To call him amateurish would have been a compliment, and we his volunteer charges didn’t really know what we were doing either. Such was the state of the entourage of the Dalai Lama during Visit One.

Today’s Dalai Lama, fourteen visits later, is still a simple monk, but he came to Washington last autumn as one of the most well-known and celebrated people in the world. His books, including a very creditable book on science, merit their own section in the bookstore now. The Washington Post publishes op-ed pieces from him on world affairs, and he is without question the leading spokesman for peace and cooperation in the world today, having inherited the mantle of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. No longer a mere inconvenience to the U.S. government, he is attended by a security and escort detail that befits the leader of a nation. When he came to the capital this time, he did not slip in through a side entrance.

In the years since my stint holding doors for His Holiness, I’ve followed his rise to prominence and paid attention to his work, but at a distance. Finally, I decided to see what the Dalai Lama road show was like these days, and how he came across in person. I chose his five-day swing through Atlanta, sponsored by Emory University, which would include an all-day meeting with scientists researching depression.

The Dalai Lama came to Atlanta fresh from his triumph in Washington, but he was not triumphal. His dignity came not from adulation and celebrity, but from simplicity. He was a human being, a Buddhist monk, a gently persuasive teacher—but also an amateur scientist, the leader of a nation, and a moral voice for the world. These are the faces of the Dalai Lama I came to know as I—and several thousand others—followed him around for a long weekend.

Warm Heart, Cool Mind: The Buddhist Teacher

When I first heard the Dalai Lama speak back in 1979, I was swept up in the spectacle of crowds streaming through the two-story colonnaded entrance to Constitution Hall, which abuts the large green space just behind the White House. His Holiness was introduced by a congressman, who mentioned that he would be visiting the Capitol the next day. It was a big deal, because for most of us Buddhists, our families had treated what we did as bordering on lunacy. The Dalai Lama’s reception in Washington somehow made it more legitimate.

The Dalai Lama conducting a Vajrayana ritual at Bokar Monastery in northern India. Photo by Don Faber.

The talk itself I forgot completely. He spoke mainly in Tibetan, so you couldn’t quite sense the whole package, the intonation and the passion behind his message. He was a personage with something to say, but I didn’t connect with him as a teacher, really. As it turned out, the talks he gave on that tour had been strategically planned to form his first book, Kindness, Clarity, and Insight, which introduced him to the world as not just a kindly figurehead but as a genuine Buddhist teacher. As I now read the Constitution Hall talk, the first in the book, I’m struck by the consistency of his message from then until now: “…in my simple religion, love is the key motivation.”

The message may be the same, but I saw a different Dalai Lama this time. For one, the spectacle has changed. The Dalai Lama is a much bigger deal now. You sense something going on from miles away. Traffic changes. As you get closer you see lots of security, and long lines waiting to pass through metal detectors: no bags, no umbrellas, no metal objects whatsoever. There are T-shirts, commemorative books, and souvenirs aplenty. The gymnasium/conference hall at Emory University, where His Holiness gave a morning address to Atlanta’s Buddhist community, was filled to near capacity. You simply joined the river of people—about four thousand—and were carried along until you eventually found yourself in a seat.

Of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the Gelugpa, the one the Dalai Lama belongs to, is best known for study and analysis. While meditative experience and devotion are not absent, they’re not emphasized as strongly as in the other schools. In the view of some, this leads to dry scholasticism. Indeed, many Tibetan teachers speak of wild Indian mountain yogis as their principal forebears, whereas the Dalai Lama evokes Nalanda, the great Buddhist university of ancient India. In the talks I heard, though, the Dalai Lama married the edge and sparkle of intellect—the glistening sword of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom—with a practical sense of urgency. He encouraged students to cultivate a cool mind, not obscured by overheated passions and delusions, and a warm heart, radiating to others a motherly kind of love.

The warm heart is what I expected in an introductory talk. But after giving a jovial and animated preamble for about twenty minutes in English, with his voice changing pitch and intonation in modulation with his gestures and facial expressions—a consummate yet utterly natural performer—he switched to Tibetan and deftly unpacked the following line from the Prajnaparamita in 8,000 Verses, a seminal philosophical work on the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness: “Mind is devoid of mind, for the nature of mind is clear light.”

He broke this one verse into three parts. He explained that “mind is” tells us that mind, the source of pleasure and pain, and therefore suffering, is something we must attend to urgently; “devoid of mind” tells us that while we might try to treat mind as a concrete thing to be cured, there is in fact no such thing as mind to be found anywhere; and “for the nature of mind is clear light” tells us that when we see mind as insubstantial, dependent on relationships for its momentary existence, we come to know that mind is pure and pristine.

“So, all finished,” he said, and let out a big laugh as he rocked back and reared up. I had been peering over the video technicians’ shoulders, watching the Dalai Lama on eight screens. At that point, I had to grope for my seat in the cool darkness to take in the moment: “Did I just hear all of the buddhadharma in one verse?”

The following day, he was installed as a Presidential Distinguished Professor at Emory, to carry further the relationship started in 1998 with the Emory–Tibet partnership, an interdisciplinary program that fosters a dialogue between Tibetan and Western disciplines. During the ceremonial parts of the event, he was duly professorial at turns but also impish and playful, almost doing shtick. If one of the many presenters fumbled with their script, he held it for them. At the critical moment in the ceremony the university president was unable to juggle both his microphone and his text, so His Holiness held the mike. For a moment the president just burbled, disarmed. But when it came time for his lecture, the Dalai Lama propelled us into a deep Buddhist analysis of cause and effect. They depend upon each other, he said. It’s not as simple as effect follows cause. They transcend temporality. Furthermore, there is no present moment that we can locate (try it), and therefore no past and future.

Just like that: There is no time. The assembled luminaries, and the ordinary folk like me, were flummoxed. It was more than a semantic trick. He meant it. I was starting to get used to the DL one-two punch: disarm and dismantle. Warm heart, cool mind.

Beyond Enemies: The National Leader

Joseph Stalin famously quipped, “The Pope? How many divisions does he have?” The Dalai Lama commands the same number (zero), but the similarity ends there. The vast land of Tibet, its 2.6 million population, and the 130,000 exiles in the Tibetan diaspora are not at all like the urban enclave of the Holy See. The Dalai Lama is more than a spiritual leader. He leads a nation.

The Dalai Lama at the Capitol Building after receiving the Congressional Gold Medal in honor of his struggle for Tibetan freedom. Photo by Don Faber.

His role could not be more complex. It was indeed a shining moment when he received the Congressional Gold Medal in the Capitol rotunda, in the presence of Congress, the president, and a large delegation of Tibetan luminaries. It’s a great recognition of the people he leads and represents to the world, but as I watched him during the ceremony (on video) he seemed awkward at times, maybe even more disarmed and disarming than usual. One can’t say, but perhaps part of that unsettledness comes from knowing that as great and numerous as the accolades he receives may be, the condition of the Tibetan nation is dire. While Tibet is more open than in the past and religion can be practiced more freely, its future is at best uncertain and at worst very, very bad.

While His Holiness may be carefree (“If there is a solution for a problem, no point in being overwhelmed and worrying, and if there is no solution for a problem, no point in being overwhelmed and worrying about it.”), he clearly cares. He wakes up each day and goes to bed each night as the leader of a people who are losing their country, and, increasingly, their culture. He faces the goliath of China and the confusing bureaucracy of India, and must navigate the byzantine relations between these two emerging giants. While highly respected now by liberals and conservatives in the West, he knows that the traditional Tibetan government he inherited was authoritarian, and at times corrupt and oppressive. Ironically, it is quite possible that had Tibet remained independent, the Dalai Lama would not be celebrated as a great world leader, but as an antiquated theocrat. He knows that the toothpaste cannot go back in the tube: the Tibetan government of the future cannot be the Tibetan government of the past. It is not even certain what “Dalai Lama” will mean in the future, and how one will be picked.

When it comes to resecuring the homeland, His Holiness’ middle way of nonviolence has come under fire from a segment of Tibetans, particularly young people, who are restive and want to see more action. The Dalai Lama listens to the pleas of the impatient and takes them to heart, but he knows the stakes and the constraints. This is a man who looked into the eyes of Chairman Mao. That must have been sobering. As I watched him spread the gospel of peace and cooperation, I couldn’t forget that he is a national leader without an actual nation. How unsettling must that be? How groundless? Would you not become despondent, resentful, resigned? In his case, apparently not, because he is a politician who does much more than pay lip service to “spiritual values.” When he says, as he did at Constitution Hall, “Your enemy can teach you tolerance whereas your teacher and your parents cannot… an enemy is actually helpful—the best of friends, the best of teachers,” he means it. He exemplifies it.

An Insatiable Appetite for Inquiry: The Amateur Scientist

To call someone an “amateur scientist” may be dubious, damning with faint praise. But the Dalai Lama is an amateur in the etymological sense: one who loves. He loves science because he has the relentlessly inquiring mind that marks a real scientist. He acknowledges that he doesn’t have detailed training in any discipline of Western science—and doesn’t have the time to take up such training—but he deeply believes that Buddhism and science must talk to each other. As two great traditions of inquiry, they can help each other make important discoveries.

The Dalai Lama discussing the treatment of depression at the fifteenth Mind and Life Institute meeting in Atlanta. Photo by Miguel Rovira, The Emory Wheel.

The Dalai Lama’s engagement with science goes back to his early days in Tibet, when he fiddled with some of the few machines that made their way into the country. He loved to disassemble watches and clocks and put them back together, very much as he likes to disassemble the notion of time itself. Once in exile, and particularly as he made his way to Europe, he was struck by the influence of science on how people lived and how they thought. Even the notion of a solar system was a foreign concept to him, but he made up for lost time, engaging leading scientists and philosophers such as David Bohm and Karl Popper in deep and lasting discussion. He started with physics and cosmology, but eventually his major focus, particularly in the Mind & Life dialogues that began in 1987, became the mind and brain, the area where he thought Buddhist insights had the most to offer to the West.

The Mind & Life dialogue in Atlanta, the fifteenth in the series, was called “Mindfulness, Compassion, and the Treatment of Depression.” A panel of scientists semi-circled the Dalai Lama, giving and listening to presentations and then discussing their implications. The presenting scientist sat next to His Holiness and essentially tutored him on the topic at hand, aided by sophisticated visual aids, while thousands in the audience looked on. It lasted for a day, and it was real science. I had trouble following it all, and my attention waxed and waned.

Fortunately, as I was reeling from too many long, Latinate words, I befriended an Atlanta psychiatrist and researcher who is also a Buddhist, Dr. Craig Johnson. He talked me through the proceedings and gave me an insider’s view of things. Like almost all scientists, he was skeptical about hype and thought some of the research concerning advanced meditators missed the point. “What matters to me and why I am here,” he said, “is not to marvel at what very advanced practitioners of mindfulness and compassion can do. I’m interested in how we can help all the people I see with debilitating brain disease. Some of these researchers are showing that even a little bit of meditation can help with that.”

It became clear that the Dalai Lama’s interest in science sprang not only from his insatiable appetite for inquiry—as evidenced by the pointed questions he asked—but also from deep caring. Buddhism offers science a spirit of inquiry married to deep ethical concerns. He believes that science, in concert with what he calls “secular ethics,” can help to make a better life, but it can ruin us as well. That’s partly why he wants Buddhist monks to receive modern scientific education, and during this visit Emory presented him with a textbook in Tibetan and English—years in the making—that offers a basic science curriculum for monks. He wants them to be conversant with the Western worldview and the opportunities and pitfalls of science. To be relevant, they must speak the language of the West, and an important part of that language is science.

What impressed Craig Johnson was the Dalai Lama’s courage in diving into science with an open mind. “So many of my fellow Buddhists are afraid of the brain and the Western approaches to it,” he told me. “The specter of determinism scares them to death. His Holiness has no fear of determinism, so he has no fear of the brain. He can take it on face value, as part of the causes and conditions. I wish I could say that about many of my fellow practitioners, who seem not to like evidence and are willing to get by on imaginary notions too much of the time.” Indeed, when the Dalai Lama looked at detailed images of the brain, he knew exactly what he was looking at—and what he wasn’t.

“I Love Him So Much”: The Voice of Peace

Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park was built as the “town square” for the 1996 Summer Olympics. When you arrive in its environs, you feel you’ve at last found some peace from the sprawling, traffic-congested megalopolis that surrounds it. The Dalai Lama’s public talk on the final day of his visit drew thousands of people from all over the South. Welcoming him, Emory board chair Ben Johnson said the park was a celebration of what was possible for human beings, since Atlanta had partly been chosen for the games because “a city that had once been a hallmark of ethnic division had come to symbolize the degree to which racial harmony can unite a city.” It also represented, he said, the pervasive impact of violence on our world, because it was here that a bombing by an anti-abortionist killed two, wounded more than a hundred, and ruined the atmosphere of the Olympics.

The Dalai Lama calling for “inner disarmament” at Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta. Photo by Eric S. Lesser.

When Congressman John Lewis took the podium, he received thunderous applause. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, he was chair of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, and he has served continuously in Congress since 1986. In the ringing oratory of a more hopeful period, he welcomed the Dalai Lama “to the hometown of Martin Luther King, the leader of the modern-day movement for peace and non-violence in America.” When he and His Holiness hugged vigorously at the end of the talk, and when His Holiness began his remarks with a tribute to King, many people were crying. As the Dalai Lama raised his joined hands above his head—his method of embracing large groups of people—you could sense the warmth coming back. By relating directly to the place, the people, and their history, he made it homey, not generic. He held the huge crowd in his hand. The woman next to me blurted out, “God, I love him so much.”

He talked about “warm-heartedness” repeatedly, about his mother, about all our mothers, about how we must teach young people not just to be smart but to be compassionate, that America is a great country but an arrogant one, and it should vastly expand its Peace Corps. He switched between Tibetan, with the words coming out of his translator flowing and erudite, and English, with words that were basic and homespun. He would stop and tap his head and say he forgot what he was going to say, and the crowd laughed and loved him more for being so ordinary. He spoke of the new century as a time for dialogue and “mutual victory,” rather than mutual destruction. Above all, he called for “inner disarmament” that will lead to “external disarmament.”

As I wandered from the park, I thought about that disarmament, because “Mr. Disarming” had become my label for the Dalai Lama. I thought about the high bar he’d set for himself as a world spiritual leader, and the desperate facts of the nation he leads, and I realized that the Dalai Lama really is just like you and me, as he so often says. He faces many deep disappointments. Things in the world often do not go the way he would like. But when that happens, he renounces the struggle to make things other than what they are. He lets the way things are become his path. That’s what a monk learns to do. And that’s why the Dalai Lama is a man of peace.