Uncle Ian sat so still listening to records, reading, drinking water. When nine-year-old Michael Stone was with Ian, he had enough space to think about the world in new ways.

Illustration by Kim Rosen.

I was nine years old and it was after school — a snowy Tuesday in January 1983. The sidewalk was covered in salt and ice, and the three women at the corner were wearing sandals, hospital-issue green pants, and only one had a coat — maroon, stained, and far too small. She recognized me and ushered me over the slippery streetcar tracks and into what was the main foyer of Canada’s largest mental health institution, 999 Queen Street West in downtown Toronto. I thought I heard he’s waiting for you but the woman was also mumbling something else to the streetcar driver, her pointed cigarette holding up the traffic for me.

I made my way through the main hallway where the nurses buzzed me in and I took the stairs to the second foyer in the northwest ward, the only ward with hallways that were clean. The green paint was peeling from the walls by the washroom and the metal corners of the drywall were cracked. I found my uncle waiting on a blue chair, smoking under an oversized clock. I wondered if he’d been waiting in that spot all day. His thin right leg was crossed over his left and then wrapped all the way around his ankle, as if his legs were made of string. He got up quickly and walked me to another smoking lounge, this one with a stereo and meditation supplies. The windows were filthy.

“It’s snowy,” I said.

“I know. I see it too, Michael. Here, help me with the records.”

I had no idea who the Buddha was but it didn’t matter; everything my uncle read seemed true. True, not because he told me it was true, but because he wanted me to think about it.

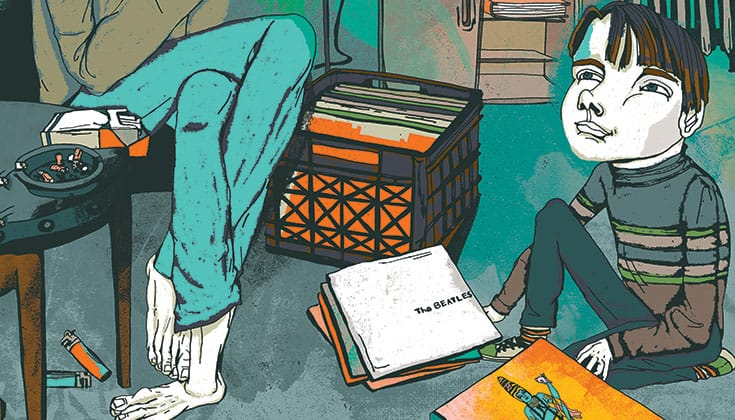

I pushed two milk-crates of records against the stereo cabinet and lifted out the worn copy of The Beatles’ White Album with the name Ian written on its blank white cover, and a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, which my uncle referred to as “yoga.” Above the stereo were two cartons of cigarettes, a collection of wasted lighters, a lamp with no bulb, and a book called the Dhammapada. I had no idea who the Buddha was but it didn’t matter; everything my uncle read seemed true. True, not because he told me it was true, but because he wanted me to think about it.

“Did you get a new book?” I asked, sounding out the word, dha-ma-pa-da.

“It’s used. It’s new but it’s used.”

“What is it?”

“It’s used, yeah it’s used. But actually it’s really ancient. Really used. But it’s also new. It’s always new.”

“What is it?”

“It’s the teachings of the Buddha. When we finish the Gita, we’ll read it. Maybe the Buddha is clearer about not being asleep. His basic stance is that if you can let go of what you are holding on to too tightly, things will be a lot more peaceful.”

Ian put on the White Album, placed an ashtray on the lefthand speaker, and announced, “This side is the drums and bass.” We angled our blue chairs to face the left speaker. Then he lit a cigarette (there was no incense allowed in the hospital) and balanced the cigarette on the rim of the burned plastic ashtray. The trail of smoke rose toward the ceiling lights. Ten or fifteen other patients were sitting in the room with us but I only noticed Ian. It felt like we’d been here since I was born. I felt normal here. I liked watching him. He sat so still listening to records, reading, drinking water. He always wanted to know what I thought and it made me feel like what I thought mattered. When I sat there with him I had enough space to think. Sometimes I could actually see the thoughts themselves lifting off of a giant unrolled banner of language and then when I had a thought I could see it go all the way down again, down onto the same dark ribbon.

As the music began we watched the rising smoke ripple into shapes above the speaker. Every drumbeat created a break in the smoke stream and the bass line made circles. Visible sound. We listened to the whole record like this.

The doctors left us alone because Ian could get all the ward’s in-patients perfectly still for an hour. Whenever I saw Dr. Walker he winked and asked me how old I was. I saw him doing some computation in his eyes but I had no clue what he thought. My grandmother had told him I’d be coming to visit Ian more regularly after school.

When the record ended, we switched to the other side of the room and listened to the vocal tracks in the other speaker. John Lennon sang about revolution. The air was thick with smoke. The nurses came in to check on me. Two of Ian’s friends, both named Paul, turned the lights off. There was some shuffling as we moved our chairs over to the right-hand side of the speaker. Another cigarette was lit and placed on the ashtray.

“In stereo,” Ian said, “you get it twice. and it doesn’t have to be at the same time. You can separate the sounds. One speaker at a time. One instrument at a time. Listen to the vocals. Study the words. Listen to John Lennon sing one line at a time. What’s he really singing about? He’s singing to you.”

When the record ended, Paul and Paul moved some chairs around. Then Ian took out the Bhagavad Gita and we read together, out loud. It was kind of like synagogue. I watched the snow falling outside and wondered why nobody cleaned the windows. I listened to the same opening lines I knew almost by heart:

Arjuna saw fathers-in-law, companions, In the two armies,

And contemplated

All his kinsmen, arrayed.

The Bhagavad Gita is a seminal text on yogic philosophy and a literary tour de force. It’s about a dialogue between a warrior named Arjuna and his charioteer, Krishna, in the midst of a fratricidal war. Over eighteen chapters, Arjuna learns from Krishna how to take action in a war that his family considers just but that his heart cannot commit to. This eternal dilemma — how to navigate impossible choices, how to take ethical action in the midst of great violence — is the focus of the dialogue and was also the focus of my endless debates with Uncle Ian.

“Why does he have to fight?” I asked.

Ian put the book down and lifted his glasses with a finger. “If he doesn’t fight it will be violent.”

“But if he fights it will be violent.”

“I know, I know,” Ian said, “but Arjuna is standing on the battle field and he has to do something. So do you.”

Illustration by Kim Rosen.

Standing on the battle field between two armies, with storm clouds gathering, Arjuna looks out and is terrified by what he sees: acaryan, matulan, bhratrn, putran, pautran, and sakhin— teachers, uncles, brothers, sons, grandsons, and good friends— all divided against one another. In the moment he is called to lift his sword and wage war, he is caught by the known faces gathered around him.

“Arjuna,” my uncle said, “has to do something. The thing is, maybe everyone is asleep. Maybe everyone is too sleepy to see what they have to do.”

I saw Arjuna in the schoolyard, in the snow, in the hospital, everywhere. I saw him filled with anxiety and the pressure to fight. Some kinds of confusion are anxious and some totally debilitating. Arjuna faces the warriors and becomes short of breath — a kind of disorientation mixed with compulsion — for he is a warrior and his training has been to fight the just war. Arjuna turns to his charioteer and says:

My limbs sink down,

My mouth dries up,

My body trembles,

And my hair stands on end.

Quivering and unable to hold his own bow, Arjuna takes a final survey of the scene and drops his weapon. He feels his skin burn, his mind ramble. Arjuna says to Krishna:

I perceive inauspicious omens,

O Krishna,

And I foresee misfortune

In destroying my own people in battle.

During the years of grades three, four, and five, I visited Ian every Tuesday. For those three years, Ian only left the hospital on Fridays when we had sabbath dinner at my grandmother’s. Her house had eleven bedrooms and sat on the top of a hill overlooking a busy street to the west and a ravine to the south. It had a massive central staircase with banisters carved from long pieces of cherrywood, art in every room, and a secret chamber behind a revolving bookcase in the study. There was a makeup room where my grandmother put on her makeup for hours in the morning, and another room, full of windows and long curtains that had a record player and an eight-track system, where Ian smoked and listened to records with my brother and I, asking us what the music was all about.

For the time being, my uncle is schizophrenic and I am not… And sometimes he is the sanest and wisest person I’ve ever known.

My brother has grown up to become a musician. I’ve trained in psychology and have found myself teaching yoga, Buddhism, and social action. In some ways I’ve never left the music room or the hospital or those endless conversations about what to do with a life. Every Tuesday since then is gone. In a way, the past gets swallowed up and can never be retrieved. And in another sense the past actually doesn’t go anywhere. Time doesn’t pass. It can’t. What is it that’s passing? I miss Ian.

The real tempo of time is too rapid for a mind to capture. Things are here only for the time being. For the time being, my uncle is schizophrenic and I am not. But sometimes I also feel insane. And sometimes he is the sanest and wisest person I’ve ever known. Sometimes Arjuna is a warrior, but at a confused moment on the edge of battle he is a person and so are all the others on the battlefield — and in the asylum. Arjuna didn’t realize until now that enemy soldiers were people too. Maybe schizophrenia was not an underlying trait sitting in Ian’s brain like damp sand. Maybe in some situations Ian was sick and in others he was just fine. Ian’s brain was like mine: a vast underworld made of tangled thread. But somehow he could think clearer than I could and was saner than my parents, so I spent all that time with him.

Maybe freedom is sensing the actual foundation of life.

Cold, damp, alone — these moods move in sometimes. Maybe Ian felt this way too. I light a fire to get warm. Less than an hour passes and the sun grows warm against the spiral chestnut grains on this desk. Maybe “not being asleep,” as Ian liked to say, is the oscillation between the hard feelings of being utterly alone and at the same time interconnected with everything else. Maybe freedom is sensing the actual foundation of life. Ian was so kind to everyone in the ward, and I entertained the idea that he was making everyone better just by his kindness. If we are all as tangled

As Arjuna comes to realize, as the Buddha teaches, as John Lennon imagines, then what good is it for any of us to pursue self-centered paths of happiness? While my parents were keeping up with the conservative values of a 1980s upper-middle-class Jewish neighborhood, I was studying my mind in the green walls of my uncle’s hospital. It was home. His record player, tobacco incense, and filthy water glasses were my private symbols of freedom.

Illustration by Kim Rosen.

When Ian was fifteen, he learned that John Lennon was studying yoga with Mahesh Maharishi yogi and he decided to look up the texts that The Beatles were reading, which is how he found his copy of the Gita. in 1968, the same year The Beatles were in India, Ian was making experimental films, playing piano, and ingesting LSD. After a year of exploring psychedelic drugs and reading fairly advanced philosophy, he had a psychotic break that nobody in the family remembers accurately. The story jumps ahead to him being taken to several hospitals and eventually a well-respected mental institution in Hartford, Connecticut, where my grandfather was told Ian was schizophrenic and would probably spend the rest of his life institutionalized.

To be alienated is to be compartmentalized, estranged, heretical. The alienated are the ones who can’t be integrated but need to be included, who we include by excluding. My mother once said the family thought more about Ian when he was away from them, making him a central figure around which the family story pivots. Through language, we cast judgment on people, lock them up, treat them, hide them, group them, exclude them. It’s as if there are “things” that exist that we don’t see we’ve created with words: homosexuals, depressives, compulsives, psychotics, neurotics, schizophrenics, suicidals. We are word addicts in our attempts to keep things at bay. The spectrum of suffering is vast because the possible scenarios our mind can enter are equally vast. since we can only truly be cured by something through entering it fully, maybe healing and torment always go together. I was five when I decided to stop playing cards before Friday night dinner and listen to music with Ian instead. my grandfather, Ian’s father, was taking lithium for his endless depression and spending only a few hours a week with his kids and most of his time alone in his study. He died a year later.

Now, just this past summer, I painted a Japanese paper scroll and glued it to the thin base of a lantern. It was the night of the Hiroshima memorial and also Obon, the traditional day in Japan to remember the dead. My teacher Roshi Enkyo O’Hara and the sangha of the Village Zendo painted lanterns with the names of those we’d loved and lost, and at sunset, we drove the lanterns out to a river near the retreat center and let them go in the slow dark currents. My lantern had my uncle’s name written across it with long brushstrokes. The one next to mine had a painting of Amy Winehouse. The river carried the glowing lanterns around the bend, and off in the distance the sky carried the long sirens from a summer training session at West Point. We chanted the Heart Sutra. Gone, gone, gone beyond. We brushed off mosquitoes and watched each other watch the lanterns sailing off. Gone.

And actively here.